“Prices are various and range from 10 to 9,000 euros. There are no products available at less than 10 euros, as economics needs to be considered, which is very important in this process.”

Ortotip, the startup company from the Prekmurje region, which is specialised in the future technology, has received acclaim from the Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Slovenia for their teaching tool “Ciciprinter”.

Despite the fact that in Slovenia quite a few companies are specialised in 3-D printing, only Ortotip provides professional services. We invite you to read the interview with the company’s sales director Ms Tjaša Zupančič Hartner, and the young engineer Mr Miha Gotlih.

You’ve received the Silver Innovation Award by the Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Slovenia, as well as a special award, for being one of the most innovative companies. What was your main goal when you started developing Ciciprinter?

TZH: The idea was to develop a teaching tool for acquiring competences of the 21st century. If we don’t educate people on the advantages of the new technology, we can’t expect them to use it.

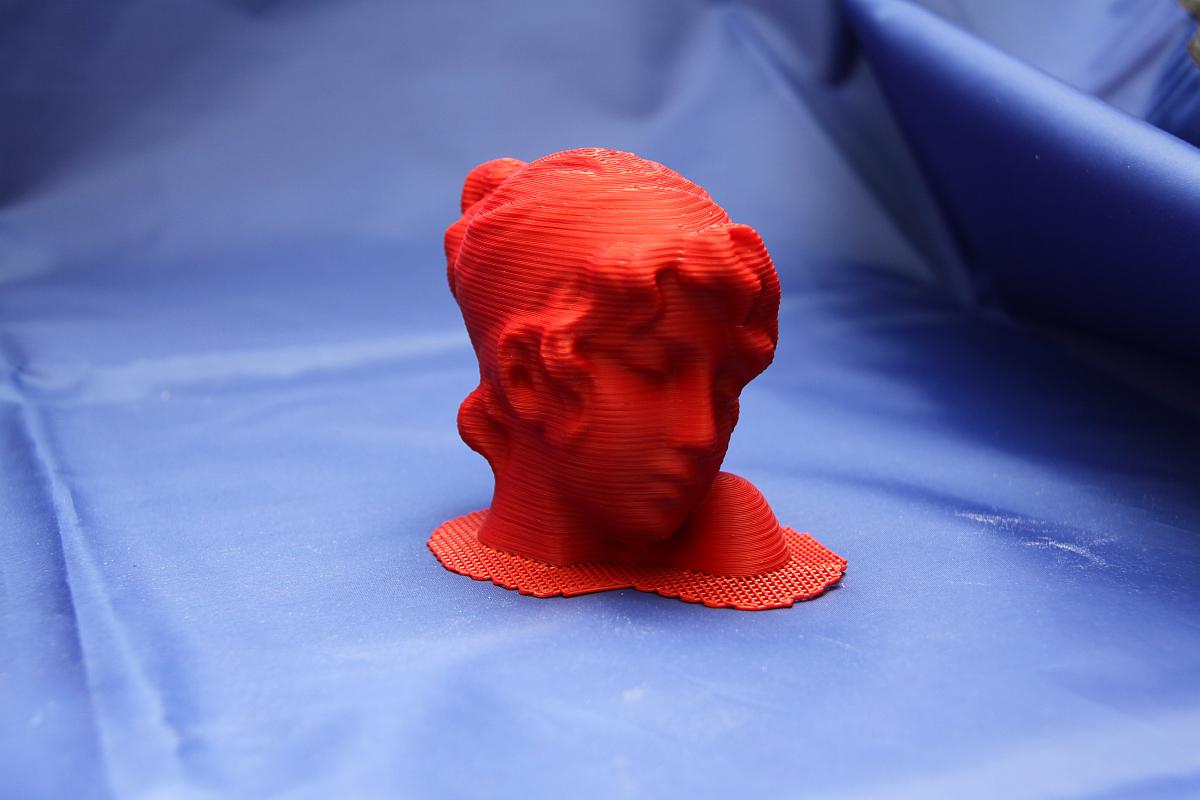

The advantage of the 3-D technology is that we no longer think of where to develop a product, but how to draw it. If the young grasp the concept, we will get into a new way of thinking about technology. On the other hand, increasingly more young people sit in front of computers creating their imaginary heroes. Using a 3-D printer, they will be able to print them, too.

How much time is needed to develop a product like Ciciprinter?

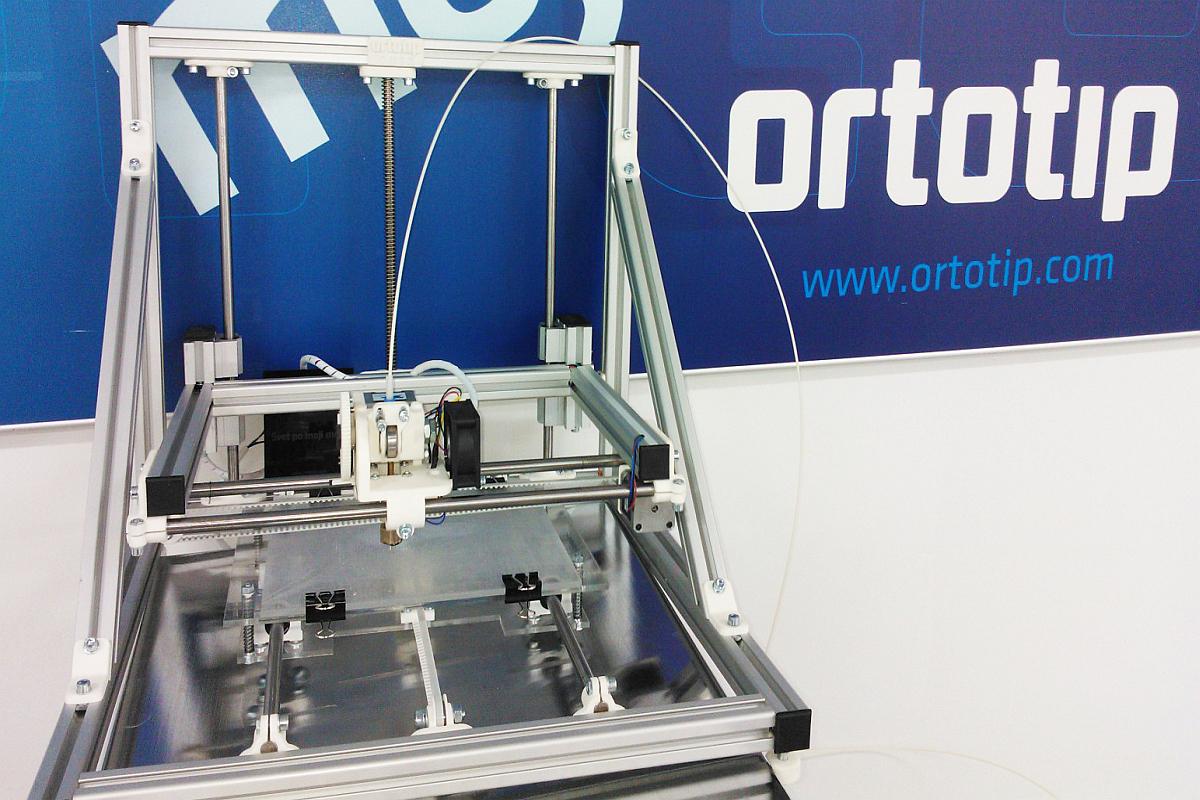

TZH: Ciciprinter was a side product of a bioplotter, that is a 3-D printer, which we are developing for use in medicine. The project is still running, as the bioplotter is a very complex product made of materials used in medicine.

But, you did develop Ciciprinter by yourselves?

TZH: Excatly, Ciciprinter is our product.

What are your medium- or long-term plans for Ciciprinter?

TZH: Ciciprinter is going to stay as it is, for our aim was to inform about what and how can be done with a 3-D printer. We are aware of the fact that, with the price, we wouldn’t be competitive in world markets. This is just one development path of our company. We no longer intend to make profit on Ciciprinter, but to lend it to schools and others. Anyone can borrow Ciciprinter from us for, let’s say, 10 or 14 days. At the moment, four Ciciprinters are available.

At first we thought Ciciprinter would become a commercial product, but it turned out that a lot of money would have to be invested, which we didn’t have. We decided to invest in buying great-size 3-D plotters, and to extend and apply our knowledge.

How is 3-D printing developed in Slovenia? Is it widely used?

TZH: The development and technology centre of Zasavje has a printer similar to ours; moreover, there is another similar printer in Slovenia. The difference between ours and theirs lies in the size of the working chamber. Our chamber is 540x540x460mm in size, and is fundamentally bigger than any other chamber. In addition to this, we have an additional machine in which various materials can be used. This makes our production more competitive. Besides, we provide counselling services for companies, and try to advice people in respect to the function of the final product.

What is the demand for 3-D printing in Slovenia?

MG: This partly depends on seasonal activities in development companies, and development departments of bigger companies, where greater needs exist for prototypes and small-sale products. Other clients include various artists and designers. However, random people may search for a replacement part, which is no longer available at the market.

TZH: This is also one of the things with which people are not familiar yet. For example, a machine part breaks, and you can have it drawn and printed in the 3-D technology.

MG: We offer a wide range of services to fulfil the industry needs. There are several possibilities for using the printer, for example in industries where plastic is used, and where people want the improvements.

Is your product available at the Slovene market only, or do also you have customers abroad?

MG: Our customers come from all countries. However, we mostly supply the Slovene market, but receive inquiries also from abroad, like Austria, Germany, China, Slovakia and Croatia.

Do customers find you and tell you what they want? Do they come with their models already drawn, so that you just print the desired product?

MG: Both is the case. Development departments already understand our needs, and we understand theirs. This means that in 99% of cases we get a model for the desired product. On the other hand, there are many customers who come with ideas, so we launch a new project every week. They come with an idea, a working drawing, a plan, a photograph, and more. We conceive a plan and a model, and a first and second (improved) version.

How much time does it take to make an average product for your customers? How much does such service cost?

MG: It’s difficult to define the cost in terms of time, as several products are being developed simultaneously. The overall duration involves the warming process, and the machine produces approximately 6–7 millimetres of layers in height, so it depends on how long it takes to make a finished product.

Finally, the process of cooling takes place, so that products don’t bend. This means altogether from 24 to 64 hours, and approximately the same amount of time for cooling. Prices are various and range from 10 to 9,000 euros. There are no products available at less than 10 euros, as economics needs to be considered, which is very important in this process.

Which experts work for a company like Ortotip?

TZH: There are mostly engineers employed, but we also have economists and a construction engineer. I’m a professor of biology and chemistry, and I’m finishing doctoral studies in materials used in medicine, at the Faculty of Mechanical Engineering in Ljubljana.

I would like to stress that in Slovenia there are many non-professionals involved in this business.

It’s characteristic of the Slovenes to know everything, to sell everything and to be the best. By this, the price of our, professionally developed products, is lowered, as people don’t consider the quality of the final product. We have already reached the limit when we said we wouldn’t undersell our products, even if the machines didn’t work. You simply can’t lower the price.

What can you say about bank financing in Slovenia?

TZH: Our banks show no support for such projects, as the interests are too high. If it wasn’t for our investor, Ortotip would no longer exist. At the moment, we are not repaying the loan by our investor, but are merely covering the costs.

How do you comment the current economic atmosphere? Does it have a depressing effect on young companies?

TZH: Not really. Our only concern is that all the young will leave us. In our company, approximately half of the employed are aged 40–50, and the other half is represented by those aged under 30. Since we’ve invested all the money in the development, all the young receive minimal wages. We reached this agreement when they came, but we will try to change it next year. Actually, we will not try to change it, we have to change it. But a new problem arises if the taxation increases more. If so, I really don’t know what we’ll do. If, for instance, we now wanted to pay a development engineer as much as we wanted, it would cost us approximately 3,500 euros gross for a net wage of around 1,500 euros. This is the least they deserve. Nobody works for having fun, but for money, and that’s clear to me.

“Prices are various and range from 10 to 9,000 euros. There are no products available at less than 10 euros, as economics needs to be considered, which is very important in this process.”