Helena Vurnik, an exceptionally talented designer, was long overshadowed by her husband. But decades after her death, she is finally becoming recognized as an exceptional artist in her own right.

Born in Vienna in 1882, Helena Kottler was determined to become an artist. At the time, women artists were rare, and her family bitterly opposed her choice of profession. In 1907, she finally managed to enroll in art school – but not at Vienna’s prestigious Academy of Fine Arts, which was still closed to women. Instead, she enrolled in a special women’s art academy.

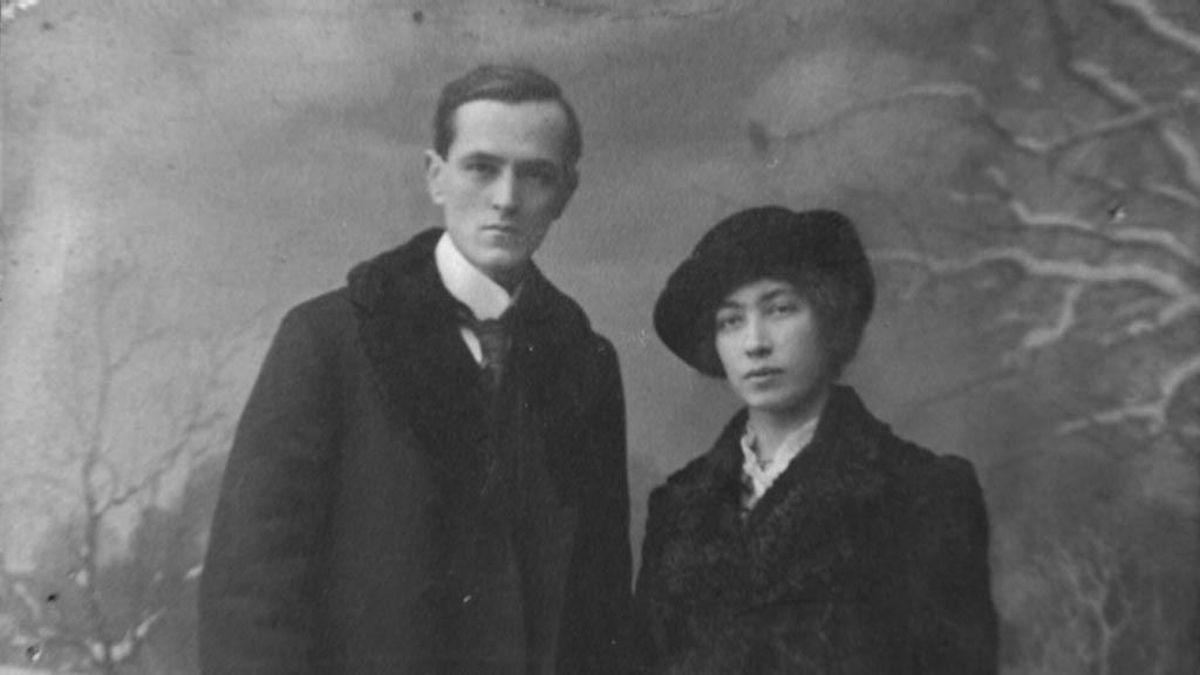

After graduation and a six-month scholarship in Italy, she founded her own studio in the Imperial capital and began to illustrate for a popular Viennese newspaper. It was then that she met Ivan Vurnik, a promising Slovenian architect. The two married and decided to move to the Slovenian Lands.

For Helena Vurnik, moving from the bustle of Imperial Vienna to provincial Slovenia was a drastic change in her life. She had a difficult time adapting to her new environment and was often marginalized as an outsider. For a time, her only commissions came from the Catholic Church; among other projects, she designed frescoes for her husband’s chapel in the port city of Trieste. She often resorted to improvisation -- she used family members and acquaintances as her models, but she also excelled in her skills: she was one of only a handful of artists in Slovenia to master religious mosaics.

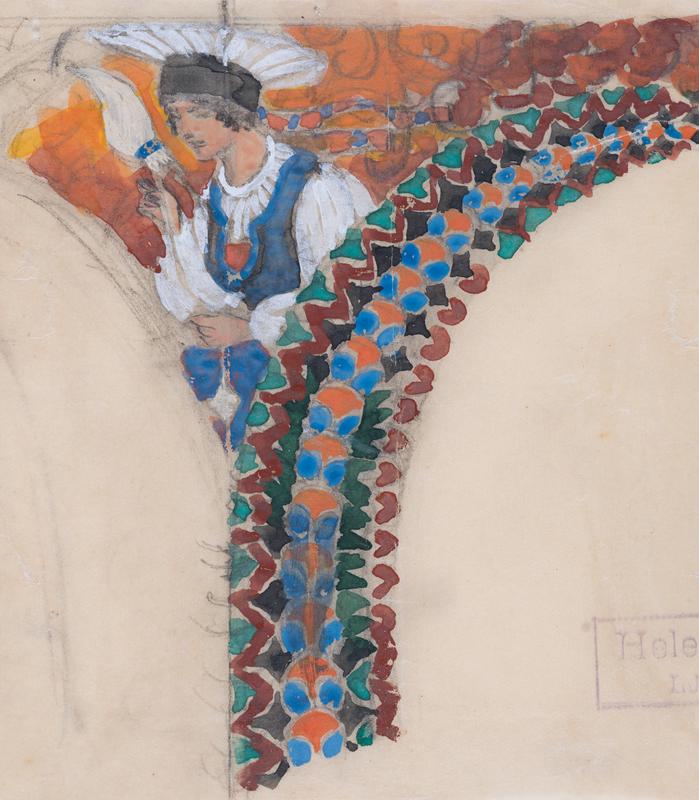

Eventually, she became more widely known for her non-religious architectural decorations, some of which graced the buildings designed by her husband, as well as embroidery for liturgical use. She developed a distinctive style that relied on folk motifs from Slovenia and the colors of the Slovenian national flag. She combined those elements with the principles of Secession, a Viennese subgenre of Art Nouveau, to create a style that was often seen as typically Slovenian.

A prime example of her style can be seen on the facade of her husband’s Cooperative Business Bank in Ljubljana. But despite the originality of her approach, her work on the building and other projects had long gone uncredited.

Commissions of Helena Vurnik’s art began to dry up later in her life. Her son was killed by the Italian occupying forces during World War II, which only added to her bitterness. She would never work on any major projects again.

Helena Vurnik died in 1962, but many of her works remained unknown to the public until a recent exhibition of her sketches, prints, and watercolors. It took the growing awareness of women in art history for Slovenia to rediscover Vurnik’s innovative yet timeless creations.