The French have no idea what was going on in our country during the Second World War, so I had to explain some concept to the readers. When considering how to do it in the Slovenian language, I had decided to do it literally, and explain who were partisans, and who members of the Home Guard, i.e. "domobranci" in Slovenian.

Tango is inspirational as well. It is not only a dance, it is a way of being. And at the same time the best manner to approach another person. The most emotional, and wordless.

"I realized how incredible those stories were. In a way – but not ideologically, or politically – we resemble each other, as I am also a Slovenian living abroad," said the writer who is living in France. Through tango, inalienably connected with Argentina, she was introduced to a new world, the world of Argentinian Slovenians. She admits that at the beginning she had no wish to get to know it. "The first time I went to Buenos Aires I had no interest in Argentinian Slovenians. I considered them traitors, collaborators… But, as Jung said, if you refuse to see something, the fate puts it in your path."

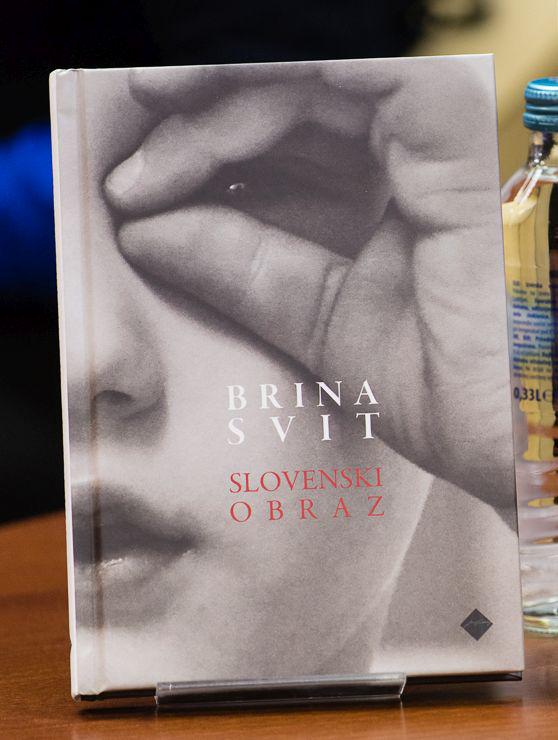

The world of Argentinian Slovenians slowly swirled around her, she became steeped in it, and the result was the novel Slovenski obraz (The Slovenian Face), a tribute to the Slovenians from Argentina. She said she invested a lot of thinking into this book. "What shows on our face, and how much of our identity. Who are we, what are we, is in a manner always projected on our face."

This time you are addressing the Slovenian readers with your new book Slovenski obraz (The Slovenian Face). It might be, in a way, the most personal book you ever wrote, your presence in it is very noticeable.

It might be so. Judging from my opus until now, I usually write two novels, and then a book which is not a novel, like Moreno, Hvalnica ločitvi (The Praise of Divorce) and now Slovenski obraz (The Slovenian Face). It seems that after a large novelistic mouthful I always return to reality, and write a non-fiction book – but I am never able to tell what it is.

While reading your description of such concepts as ‘domobranci’ (members of the Home guard), and partisans, I wondered in which manner you had approached the project, and decided on a definition of certain concepts which remain constant stumbling blocks.

As I wrote in the Preface, at first I wanted to write the book in the Slovenian language, and I intended to include the entire Argentina, not only Buenos Aires. A large number of Slovenians went south, to the Andes, looking for the familiar image of mountains. I had applied for a subvention for this book, but I was refused. So I decided against this project. But my French editor told me to write it in the French language. Of course, this book is different from the one I would have written in the Slovenian language. The French have no idea what was going on in our country during the Second World War, so I had to explain some concept to the readers. When considering how to do it in the Slovenian language, I had decided to do it literally, and explain who were partisans, and who members of the Home Guard, i.e. "domobranci" in Slovenian.

It seems this part of our history still divides the Slovenians, that we can't rise above it and see the personal stories behind it.

When a year ago the book was introduced at the French Cultural Centre, Boris A. Novak well said that he believed this book would finally end the Second World War, and encourage people to start considering the war finished. Well, I don't know if it is really so. But I must say that for me this book is, above all, literature. That's what interests me most, the sense of literature - use of literary means, form, rhythm, the adequate tone… To create an emotional reaction, and to let the reader reflect.

One of the thoughts from the book refers to the concept of a victim. The first generation which left endeavoured to preserve everything Slovenian, while their descendants, or at least some of them, have found themselves in a vacuum: they had no knowledge of Slovenia, but they were not Argentinians either.

It was the most difficult for those, the sons of their fathers - they had to obey the wishes of their parents, which not necessarily complied with their own wishes. It happened sometimes that they preferred a girl of a different nationality to a Slovenian girl, but they were not allowed to marry her - they had to marry a Slovenian girl. Not all of them had such problems, but most of them did. And that's just one example. They had to agree with their fathers’ interpretation of the history, they had to be right-wing, conservative. It was the whole package: everything of nothing!

In your book you wrote that we Slovenians worship the cult of the past, and have a good memory. Don't you think it can occasionally paralyze us?

I think it is a good thing to have a good memory, and to be able to place the thing in its rightful place. Slovenians have often withheld things, or placed them where they didn’t belong. That's the reason we keep looking back, and these things remain minefields of a sort. But we are not the only nation with this problem - for years nobody in France had spoken about the war in Algeria. Also in Argentina decades were needed for the culprits for the military junta to be punished.

The French have no idea what was going on in our country during the Second World War, so I had to explain some concept to the readers. When considering how to do it in the Slovenian language, I had decided to do it literally, and explain who were partisans, and who members of the Home Guard, i.e. "domobranci" in Slovenian.

Tango is inspirational as well. It is not only a dance, it is a way of being. And at the same time the best manner to approach another person. The most emotional, and wordless.