It might seem a cliche, especially since lately we have heard these words in one form or another quite often – of course only if we paid attention to the promotion of this large coproduction of SNG Drama Ljubljana, MGL theatre house, and Cankarjev dom, advertised as 'the biggest production of the year'. Yet Lorenci actually meant what he said, and actualised his words on stage – or should we say 'half-stage', as most of the time a part of the stage is hidden behind an iron curtain. But that is irrelevant, as the director and both dramaturges (Matic Starina and Eva Mahkovic) give the impression of broadness in another way – through the epos, in its copious loquaciousness, metrics, and the Iliad itself as the bedrock of civilisation and modern commonness. The basis of the performance hides within the core of Greekism, or in what we know about it, and the tradition of aoides sigers and rhapsodes, professional reciters travelling all over the country and propagating epic poems (Homer being allegedly one the rhapsodes).

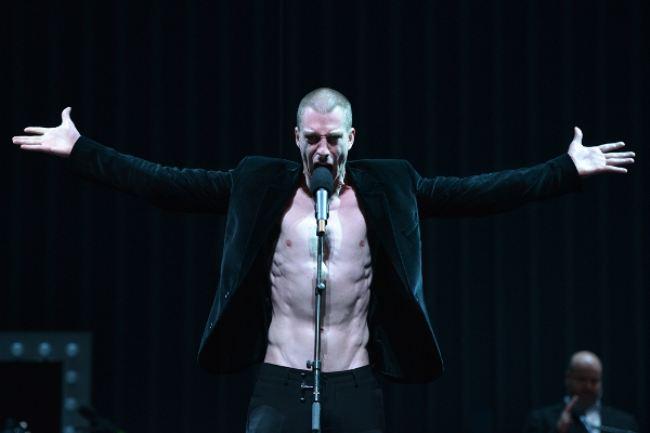

The twelve actors are arranged in a semicircle, stepping out individually, and then returning into the semicircle, while gradually familiarizing us with the happenings in front of the rampart of Troy by reciting hexameters in metrics of outmost precision. The individuality of singular roles is gradually merging into one collective, drawing the image of the Iliad in front of our eyes with the minimal use of theatrical accessories, compensated by much more intense dramaturgical means, music, rhythm, and sovereign acting. There is no need to praise separate actors, as each of them gives his/her contribution, and becomes a part of the whole – either as a character, a narrator, or just an observer. Their movement through the epic expanse, which is by very definition public and collective, is of dual nature, since the actors are at the same time narrators and actors, simultaneously a subject and an object, and that has a crucial influence on the nature of the production.

The Iliad is anything but a classical theatrical production; there are no soldiers racing up and down the stage as expected for a theatre spectacle. It is an intimate theatrical performance during which the intimate narration, in hexameters, develops into tri-syllabic dactyl, the rhythm of warfare, love-making, quarrelling and seducing, consequently evolving into music which is growing gradually louder, and forms an essential dramaturgical element of the performance. By precise and judicious use of music – from Balkan melodics to gospel, from fiddle music to Je t'aime – it helps to induce, or to dissolve tension, and becomes an integral part of the body of the actor, and of the spectator. There is no need for cavalry at the stage of the Gallus Hall, as the effective sound brings into the hall war atrocities, the very maelstrom of war, the gradually increasing insanity, which affects Hector the most. The director bets on the naked strength of words arranged in metric verses, emphasized by the monotonous, but strong rhythm fluidly flowing into music, carried by female actors. He succeeded in presenting to us the Iliad much more effectively then the big screen could possibly hope to do.

The scenography is rather ascetic, focused only on the essential accessories (a cooler, among other things), which have nothing to do with the performance. The stage illusion concentrates on the hay bales (Achilles' vision of his native Phthia); for one moment the entire stage is visible, which makes us expect that it will widen in the second part, and that after the first part is over, the battle will spread and gain huge physical power. Yet it does not. The battle with its psychological (and physical) dimensions concentrates on Hephaestus, or on the accidental hero, a collateral damage; in the background we can hear the names of the killed soldiers from Homer’s list, accompanied by music. The impact is at least equal to hundreds of helmeted soldiers fighting onstage. The Lorenci’s Iliad has no need for spectacle to be spectacular, as it does not seek grandeur in its image, but in its impact, and its message.

The interpretations of the performance are quite fluid. Lorenci again relies on merging of fragments of the motives from our present, banality (e.g. self-critical basic-animalistic, “the strongest of all!” Zeus, or ‘three minutes for Patroclus’ stage, and even somewhat cynical Achilles, yet steady as a rock), this time in reference to antiquity. The most obvious intention of the performance is to abandon solipsism (ego mentality) and enter the field of the collective. By emulating antiquity and its patterns Lorenci managed to pinpoint the focal aspiration of the present time, the aspiration for pronounced individuality, and reminded of what most people would like to forget – our transience, and mortality. The story of Achilles is less pronounced due to all the stories and motives the Iliad contains, but that is of no consequence. The message was sent – sooner or later we will all die, or, as sung at the end: "We are going to die, today or tomorrow, life is what we borrow." The pronoun 'we' can be quite easily replaced with our own name.