Apart from the fact that the volume of funding for scientific and technological research in Slovenia is low, our system also has some structural faults. Similar institutions around the world also receive institutional funding, while we obtain income only through projects, in other words, only competitively. The competitive method does have a range of good points, since it forces us to be constantly ‘in shape’, but it prevents the Institute from implementing its own development policy. The director and scientific council actually have no money available to guide the Institute, only the researchers have money for their projects.

Dr. Jadran Lenarčič heads the biggest and most influential research body in the country, the Jožef Stefan Institute – the leading body of Slovenian science. He is a doctor of electrical engineering, and gained international recognition through his research on robotics, principally investigating biorobotics and humanoid robots. He lectures at universities in Slovenia and is a guest professor abroad, and as a valued expert holds various offices in international organisations involved in science and research. He was also the initiator and head of a series of symposiums that serve to present the latest findings in the area of robot kinematics.

Lenarčič first took over as director of the Jožef Stefan Institute (JSI) in 2005. Since then he has taken part in working groups to overhaul higher education and research legislation, as well as in a number of councils in ministries and other bodies in Slovenia. In the assessment of European research institutes, universities and other organisations involved in science and research, the Jožef Stefan Institute is ranked a high 37th place. The Thomson Reuters agency, which verifies publications and citations of scientific articles, found that, compared to the German Max Planck Institute, the Los Alamos laboratory in the USA and CNRS, the most distinguished French research centre, JSI took third place after the German and American institutes, and ahead of the French one. The agency’s data shows that the Institute’s most successful field is physics, which in terms of the number of researchers employed has achieved even more published articles than the physicists from the other three institutes. JSI as a whole is also more successful in terms of how much money it spends on research.

You proposed a change to the system of financing.

Apart from the fact that the volume of funding for scientific and technological research in Slovenia is low, our system also has some structural faults. Similar institutions around the world also receive institutional funding, while we obtain income only through projects, in other words, only competitively. The competitive method does have a range of good points, since it forces us to be constantly ‘in shape’, but it prevents the Institute from implementing its own development policy. The director and scientific council actually have no money available to guide the Institute, only the researchers have money for their projects.

You strongly emphasise that an awareness of the role of science, research, creativity and knowledge in the broader sense has been lost, or at least been subsumed in all the social subsystems, and even in science itself.

Yes, that is true. Sadly the attention and functioning of Slovenian society have been redirected to what are in my opinion less important and non-developmental topics. We are occupied with more or less populist issues that attract media attention. But what we want is for Slovenians to finally focus their minds on their fate, on how to improve conditions and to involve all the potential we possess in our own development. Here I see the key role of scientific and technological research as a basis for economic and broader social development. Above all I want to experience the mental breakthrough I have been awaiting for at least 25 years.

Just these few facts point to a valued scientist whose views are always clear, sharp and committed to scientific truth.

My heart is in my work, otherwise I would not be here, that’s all. And we need to protect the best that we have. We have quite a few leading researchers and outstanding achievements that are, I would stress, not so much fruits of the system but of spontaneous ideas. I am talking mainly about the successes of individuals, and not of some organised innovative system. Basic, applied and developmental research is pursued quite randomly. Fortunately our institute goes beyond the average, but still we want the system to be set up in a more integrated way, as was set out in Slovenia’s research and innovation strategy. Of course we would need additional money for a radical change to the system of innovation. Today the cost of one coffee per month per inhabitant would cover a fundamental shift. We also need to be more aware that the results of science are not evident in the short term, this is always long-term work that usually has a lot of indirect effects. Of course, we are also not yet a knowledge-based society, in the noblest sense of the term. And local knowledge is only worth something if it can compete with knowledge internationally.

You employ young people, the most talented people with superlative knowledge, and they are ready to compete with the whole world.

The Swiss, for instance, see clearly that they will be winners if they have good science. Each individual there understands that. Here, sadly there is no such understanding. Perhaps as a nation we have trouble accepting the fact that science is in essence abstract, since it deals with something that does not yet exist, but will do later. You can only understand the role of science when you look ahead, when you have vision. And this is what we lack.

Your institute ranks among the most prominent in Europe and the world, so there are probably no major issues with regard to its good leadership.

Our institute is something special, even just because of its size. We employ nearly 1,000 people and we are the only multidisciplinary research institute in Slovenia. This critical mass of people creates a strong spirit of cooperation among different groups, some healthy competition and a constant proving of ourselves, which generates good results. We are most certainly special, since there is no comparable institute in Europe. Within Europe that makes us very strong, and in European projects we are one of the most successful partners and also the most successful in securing funds, although we operate with much less money than comparable institutions in Germany or Switzerland.

So the secret of your institute is the high motivation of the people?

Absolutely. Employment at our institute is a great privilege. If for no other reason than there is an extensive selection process before you get in here. First you have to be the best student, doctoral student and later post-doctoral researcher, then you have to have a special character, a sense of belonging to the profession of scientist or researcher, and you have to be prepared to live that character. Our institute is a truly specific environment. It comprises a mass of people involved in physics, chemistry, biology and information technology, the environment, automation, nuclear technology and so on. There are a lot of young people, and a fifth of the employees are foreign researchers. This environment creates the spirit that is not simply an institute, but the Jožef Stefan Institute.

As demonstrated, of course, by you. You are in your third term as head of JSI, and you have been employed there since the very beginning of your career, which is now winding down. Your one, first and last job.

My contribution to the Institute definitely includes loyalty. We have a saying: once an institute guy, always an institute guy. Even people who have only been here a short time like to come back and maintain ties. It is a kind of cultural phenomenon. The very first director, Anton Peterlin, said that JSI is not just a scientific but also a cultural centre. And this is one of my main missions – to make it a cultural centre. We have constantly been cultivating this spirit, in part because we bear the name of the most famous Slovenian of all time, Jožef Stefan. All over the world, everyone knows Stefan’s Law.

You speak of a cultural institution, but how close is science to culture?

Culture is all too often mistakenly understood only as art. Culture is something much broader. Our institute for instance is a centre of natural science and technical culture. Furthermore, as is well known, a major fine art gallery is housed at JSI, complete with permanent exhibitions, and we collaborate with the Ministry of Culture. Our employees become socially engaged in various events that are not just about science. We will soon be planning Stefan Days, where we open our door to the public. At such events we are not just talking about science and research; this year for instance, we will discuss the current state of Slovenian society, or real virtuality as I have called it.

Real virtuality?

We live in a time when news, aided by social media, spreads very rapidly, regardless of whether it is true or not. This becomes reality, because it has a real influence on our life, and instead of us dealing with the real, we deal with the virtual. This engenders the spread of lies and artificial self-images, where we can all be anything. This is becoming an integral part of the society of real virtuality.

You seem to be a researcher with a heart and soul.

I am truly a researcher in all areas of my life. Wherever I arrive, I start looking for changes, most especially in the sense of design. I come from the coastal city of Koper, where as a child I lived in surroundings marked by Venetian architecture. That has also fired my imagination. Even Einstein said that knowledge is limited, while imagination embraces the entire world. I also experience things in this sense – a researcher with all the dimensions elements, perseverance and dedication to work – through imagination and vision, which leads and guides you. Creativity is the foundation in science and art, since it enables outstanding achievements and breaking out of the box and into new untamed dimensions. The opposite of this is being obtuse and closed. Creativity develops better where doubt is permitted and where making mistakes is not prohibited, where there is less conformism and stubbornness, and more freedom and interchange. I see the status of a true scientist as being someone who enjoys to the maximum everything they do and constantly questions their own achievements. And the progress of the individual, group, society and all of civilisation relies on the outstanding achievements of creative people in all realms of human endeavour.

You are not one of those people who see work as an imposition.

No, no, far from it! Sometimes someone tells me that it must be hard in such a demanding job to cultivate my artistic efforts. I would simply die if I could no longer do all of that. It is my obsession, who I am.

As an amateur painter, and also a member of the fine artists society, even without any formal training in art, you probably experience the world in images.

In my head I am constantly creating images, which if I do not put them on canvas, stay in my head. I have painted all my life. It has been my love ever since childhood. I do abstract painting, since that allows me greater creativity. Images of Venetian Koper from my childhood continually appear to me – streets, houses, churches, chimneys, of which no two are the same, the sound of birds, the splashing of the waves in the marina, the smell of decomposition from the sea, the ship horns as they enter the harbour... I paint all these images and feelings on my canvases. I thought about studying painting, but I was afraid that I would lose a large part of my other talents, plus, how would I survive? I was even interested in studying philosophy and sociology, and that breadth comes in handy nowadays in establishing contact with people.

Clearly your parents did not clip your wings through the wrong kind of upbringing.

They never made anything forbidden to me. My parents were extremely interesting personalities, very sharp. They allowed and permitted me anything. It is true that as a child I would not take orders from anyone, but I always felt like an adult. At that time I did not want to be a child, but now I am increasingly recognising the child in me. I am convinced that the most creative person is the one that manages to keep the child in themselves. We were a family in which creativity was cultivated, and I am extremely grateful to my parents for this. There is greater creativity in environments where there is greater knowledge, diversity and fresh air blowing through, where there is culture disposed to the muses. Knowledge, diversity and culture are three sides of the pool of outstanding achievements. Science and art are both creative and intellectual processes. All of this is encouraged by a kind of inner muse, an impulse, something irrational. Scientists are also drawn to be creative by an artistic muse, a desire for something new that no one has yet created. This is the same process in both the artist and scientist.

It seems your fundamental method of work is the complete freedom to create, so you agree that the director should leave researchers in peace and not get in the way of their work.

And allow open discussion at all levels. I am convinced that important social issues should not be decided upon only by politicians or economists, but also people who are active in society.

How do you respond to the question of how to help the economy to become more competitive with the help of science?

Basic scientific research and linking science to the economy are key to the future development of Slovenia. Given that in our society the concept of science is conceived in very abstract terms, it is not enough to just be aware that knowledge contributes to success in all areas, including the economy, culture and social security.

How do you predict science developing in the future?

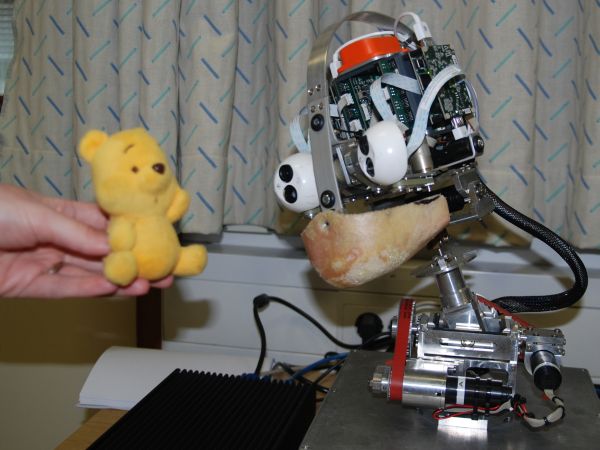

The greatest scope for development lies in nanotechnology, which offers the possibility of understanding processes on the atomic and sub-atomic levels, while robotics also has enormous development potential, since in everyday life there will be robots that are similar to people. We will see the development of a civilisation of robots that will communicate with each other, and the human-machine connection has a big future. New materials, biochemistry and information technology will also feature in this.

What are your thoughts about Silicon Valley?

I am convinced that we already have a Silicon Valley in Slovenia, or are very close to having one. I mean the Vič district of Ljubljana, since it is home to all the technology and natural science faculties, as well as research institutes. I am certain that such an area will draw in people from all over the world. We need to invest in that environment, in the infrastructure and urban planning. The preconditions are already in place – principally the people.

And your wishes for three years’ time, when you are retired?

That I will never again in my life have to put on a suit and tie. In shorts and T-shirt, spattered with paint, and a brush in my hand, I want to spend creative years with paints and enjoy it to the maximum.

At the Jožef Stefan Institute, scientists deal with mysterious nanotechnologies, biotechnologies, computer algorithms and particle accelerators. They collaborated in discovering the Higgs boson and clarifying the question of where antimatter has gone in the universe. For both they can claim a small piece of the Nobel prizes. They also created a self-cleaning cover for cotton fabric, an atlas of Slovenian science, and they the Slovenian meteorite, the Jezersko meteorite.

Three of the most prominent achievements of JSI in the past year have been in the fields of physics, chemistry and IT. The first one is the fastest computer memory in the world. The potential from this discovery is enormous, since memory speed is now the main obstacle to the further development of computers. The other achievement was in the area of piezo-electric materials, where scientists at JSI explained how their properties depend on the impurities they contain. The third important achievement was the miniature ECG heartbeat sensor, which a Slovenian company will manufacture. This is a personal sensor that collects vital data about heart function via a mobile phone. All three achievements are breakthroughs in the world of science and technology.

Vesna Žarkovič, Sinfo

Apart from the fact that the volume of funding for scientific and technological research in Slovenia is low, our system also has some structural faults. Similar institutions around the world also receive institutional funding, while we obtain income only through projects, in other words, only competitively. The competitive method does have a range of good points, since it forces us to be constantly ‘in shape’, but it prevents the Institute from implementing its own development policy. The director and scientific council actually have no money available to guide the Institute, only the researchers have money for their projects.