He spoke, and they danced on more rapidly yet, Away from the dance floor and further they whirled, Beside the Ljubljanica thrice round they swirled, Still dancing, they ‘neath the loud waters were hurled. A whirlpool was seen from their boats by some men, But nobody ever saw Urska again.

A newspaper reports: the Lippizaners collaborated on a historical film. A radio explains: a millionaire had bought the Lippizaners, the noble animals were quiet throughout the journey over the Atlantic. And a text book teaches: the Lippizaners are graceful riding horses, their origin is in the Karst, they are of supple hoof, conceited trot, intelligent nature, and obstinate fidelity.

Remember then, limpid Soča, The commands of your fervid heart: All the waters stored In the clouds of your skies, All the waters in your highlands, All the waters of your blossoming plains, Rush it all up at once, Rise up, froth in a dreadful stream! Do not confine yourself within the banks, Rise wrathfully over the defences, And drawn the foreigners ravenous for land To the bottom of your foaming waves!

No tourist guide can do as well as literature in capturing the essence of a city, landscape or neighbourhood; it is able to merge the spirit of time with immortality and it sees beyond the superficial and self-evident. If we really want to understand the places we visit, we must let literature tell of their heritage. And, of course, vice versa: in order to allow literature to breathe, it should best be read at places that have inspired its authors. So we are presenting four Slovenian poems describing Slovenia’s peculiarities. Their verses reveal more than any map, description or photograph.

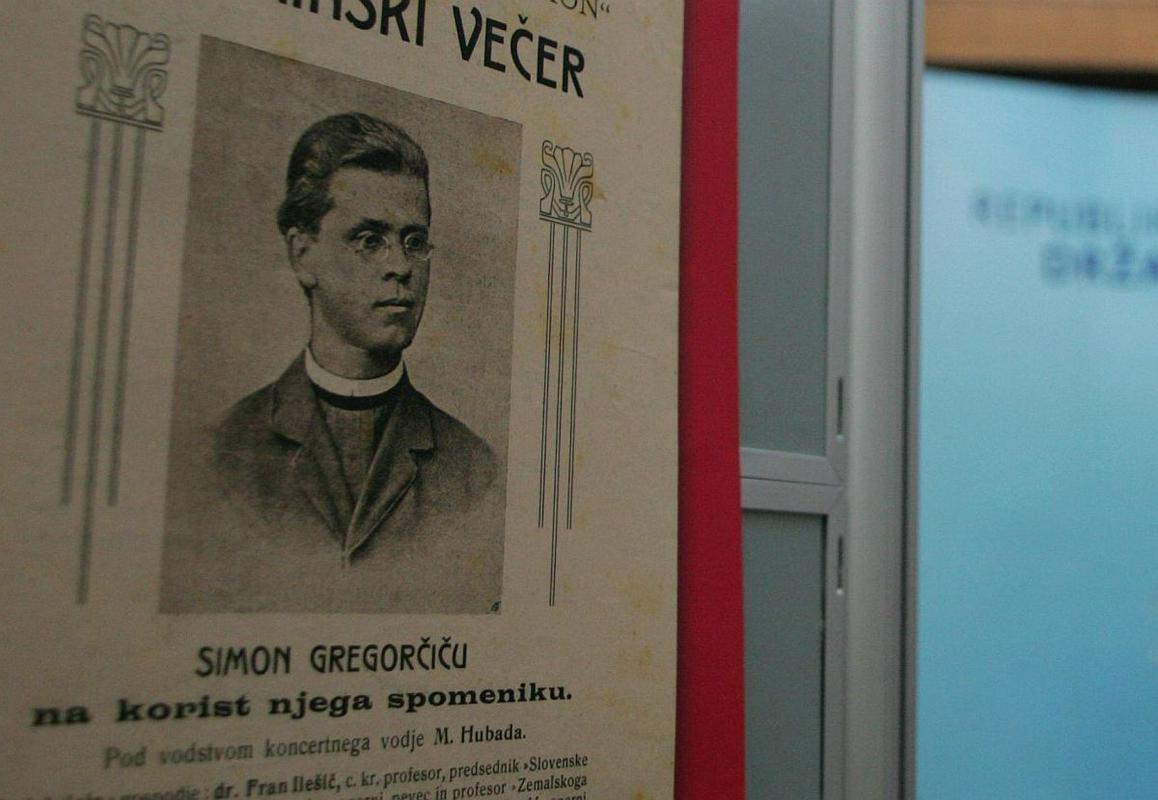

To the Soča River is a poem that must be learnt by heart by all school children in Slovenia; the same was required from their parents as well. In the poem, written in 1879, poet Simon Gregorčič praises the beauty of the emerald Slovenian river. However, behind the description of its magical beauty (the Chronicles of Narnia were filmed along the river, which testifies to it being truly magical) looms something sombre: a dark premonition that some day, the crystal-clear river will turn into a river of blood. Today, this is seen by many as a prophetic announcement of World War I, which was given more than three decades before it erupted. Namely, the Isonzo Front, the scene of the largest series of mountain battles in the history of humankind, ran through the Soča River basin. Spending time along the Soča River is as multi-layered as Gregorčič’s poem. On one hand, it offers unspoilt nature, which is a true pleasure to explore, while on the other, it reminds us that mankind is able to turn even the most magnificent place in the world into hell. (The Kobarid Museum of World War I organises guided tours along the Isonzo Front trails, which greatly present the impact of world history on the local environment: it’s a few hours’ walk from the Italian Charnel House, which was opened by Benito Mussolini in 1938, to the Napoleon Bridge, which received its name when Napoleon troops marched across it in 1750. During the walk, visitors can enjoy beautiful natural scenic views.)

A passage from the final part of the poem:

Remember then, limpid Soča,

The commands of your fervid heart:

All the waters stored

In the clouds of your skies,

All the waters in your highlands,

All the waters of your blossoming plains,

Rush it all up at once,

Rise up, froth in a dreadful stream!

Do not confine yourself within the banks,

Rise wrathfully over the defences,

And drawn the foreigners ravenous for land

To the bottom of your foaming waves!

Edvard Kocbek (1904-1981): Lipicanci/The Lippizaner

Lipizzaners are white horses that are born black. They became famous as the breed of the Habsburg nobility, trained at the Spanish Riding School, which still gives performances in Hofburg in Vienna. Edvard Kocbek devoted a poem to them, in which he says they are “white and black buffoons, the court fools of its Majesty, Slovenian history.” But Lipizzaners, which you can visit in their natural environment on the Kras plateu in Lipica, surpass Slovenian history. When you touch a Lipizzaner, as the saying goes, you touch world history. They were present at the most important weddings and funerals, Habsburg Emperors wrote decrees about them (23 directives for the breeders of horses belonging to Emperor Leopold I of Habsburg, 1658), they were given to conquerors (Napoleon, 1979), they were ridden by winners (general Georgy Zhukov at Red Square in Moscow after the end of World War II) and presented as precious gifts (Tito presented black mare, Stana, to British Queen Elizabeth and one of his stallions each to Naser and Nehru). In his poem about Lipizzaners, Edvard Kocbek shows that a horse is a synthesis of nature and world history.

A passage from the beginning of the poem:

THE LIPPIZANER

A newspaper reports:

the Lippizaners collaborated

on a historical film.

A radio explains:

a millionaire had bought the Lippizaners,

the noble animals were quiet

throughout the journey over the Atlantic.

And a text book teaches:

the Lippizaners are graceful riding horses,

their origin is in the Karst, they are of supple hoof,

conceited trot, intelligent nature,

and obstinate fidelity.

But I have to add, my son,

that it isn't possible to fit these

restless animals into any set pattern:

it is good, when the day shines,

the Lippizaners are black foals.

And it is good, when the night reigns,

the Lippizaners are white mares,

but the best is,

when the day comes out of the night,

then the Lippizaners are the white and black buffoons,

the court fools of its Majesty,

Slovenian history.

© Translation: 1977, Sonja Kravanja

France Prešeren (1800-1849): Povodni mož/The Water Man

The greatest Slovenian poet, author of the Slovenian national anthem and a strong representative of Romanticism, wrote The Water Man in 1830, in his youthful period. It is a ballad about a conceited woman, Urška, who arrogantly rejects all young man inviting her to dance. Immediately before the dance ends, she finally decides to dance with a handsome young stranger – who, as it turns out, is a dangerous Water Man, who takes her with him to the bottom of a river. After that, the woman is never seen again.

Although the poem has a tragic ending, it accurately depicts the liveliness of evenings along the Ljubljanica River: live music, blooming linden trees, boisterous dancers. The atmosphere along the Ljubljanica River is no different nowadays. On its banks, you can find everything from the botanical garden to the most beautiful square with a view of the Castle Hill, from a market with locally produced food to a flea market, from boisterous youth enjoying Friday night to placid pensioners seeking the silence of a Monday morning.

A passage from the final part of the poem:

“Fear not, fairest Urska, just keep well in step!

Fear not,” he declares, “if the thunder resounds,

Fear not that the water so noisily pounds

Fear not the strong winds with their whistling sounds;

Just speedily, speedily make your feet haste,

Just speedily, quickly, there’s no time to waste.”

“I must have a rest now, I’m quite out of breath!

Let’s stop for a little, kind dancer, my dear!”

“The white land of Turkey is not at all near,

Where Danuble is met by the Sava so clear,

The deafening waters are waiting to greet

You, Urska! so quickly keep moving your feet!”

He spoke, and they danced on more rapidly yet,

Away from the dance floor and further they whirled,

Beside the Ljubljanica thrice round they swirled,

Still dancing, they ‘neath the loud waters were hurled.

A whirlpool was seen from their boats by some men,

But nobody ever saw Urska again.

Translation: Henry Cooper

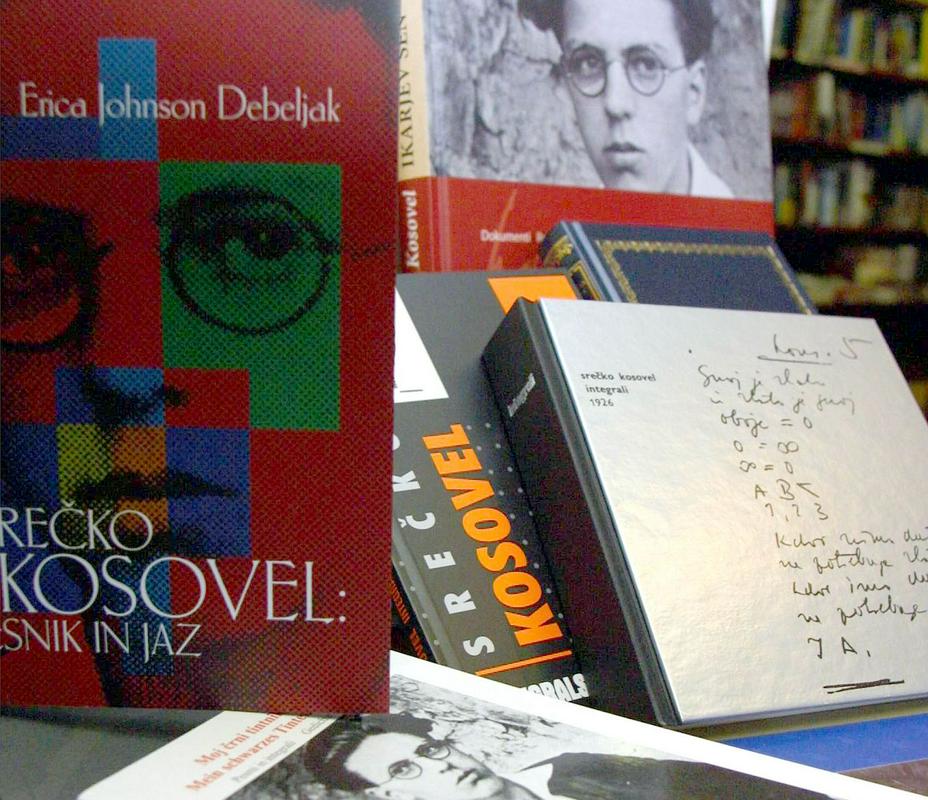

Srečko Kosovel (1904-1926): Pesem s Krasa/A Song form Kras

Kras is a rocky plateau where the impact of water on limestone resulted in the formation of various karst phenomena, including caves and other distinctive landscape features. It stretches between the Bay of Trieste and the Vipava Valley and offers a view of one of the most unique landscapes in Slovenia and the world. This landscape has also inspired poems; perhaps the most well-known example is that of Rilke, who, during a walk around Nabrežina, near Devin, where the cliffs of the Kras Plateau meet the Adriatic Sea, wrote the first verse of the famous Duino Elegies, which starts as follows: “Who, if I cried out, would hear me among the Angelic Orders?” When the sound of the Bora wind meets the roar of the sea, no cry is loud enough to be heard. The same sentiments for Kras were also felt by Srečko Kosovel, Slovenian avant-gardist who, when he wanted to take a break from the strains of society, retreated to Kras, as he believed in its health-restoring powers. While in Kras, he always felt young and healthy, full of energy for resistance. In Srečko Kosovel’s poetry, Kras is not only an oasis of peace but also an area threatened by Fascism, in which resistance must develop in order to help preserve humanity.

Sinfo

He spoke, and they danced on more rapidly yet, Away from the dance floor and further they whirled, Beside the Ljubljanica thrice round they swirled, Still dancing, they ‘neath the loud waters were hurled. A whirlpool was seen from their boats by some men, But nobody ever saw Urska again.

A newspaper reports: the Lippizaners collaborated on a historical film. A radio explains: a millionaire had bought the Lippizaners, the noble animals were quiet throughout the journey over the Atlantic. And a text book teaches: the Lippizaners are graceful riding horses, their origin is in the Karst, they are of supple hoof, conceited trot, intelligent nature, and obstinate fidelity.

Remember then, limpid Soča, The commands of your fervid heart: All the waters stored In the clouds of your skies, All the waters in your highlands, All the waters of your blossoming plains, Rush it all up at once, Rise up, froth in a dreadful stream! Do not confine yourself within the banks, Rise wrathfully over the defences, And drawn the foreigners ravenous for land To the bottom of your foaming waves!