We’re not as bad as we depict ourselves, but we’re not perfect either. We’re an average developed country, we’re not Germany or Scandinavia. Our capability is at the level of an average developed country, that’s a fact.

We shouldn’t see this as money that has been thrifted, saying ‘we’ve thrown away money yet again’. No, we’ve invested it. If this is a good investment will depend on whether or not we put the economy back on its feet. First the banks and then the economy; if the latter restarts successfully, this will be an investment that will repay the money.

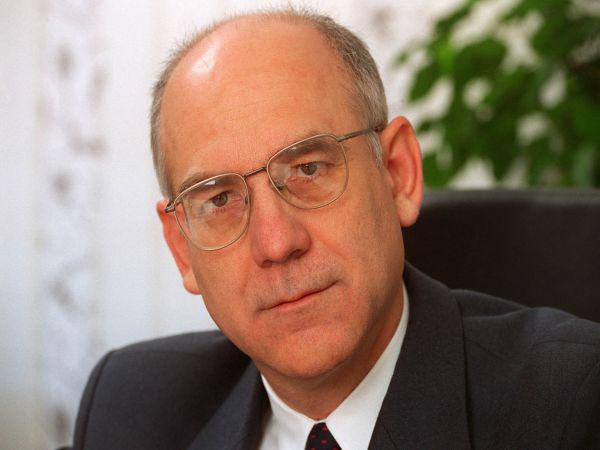

“It’s quite possible that we’ll be slightly on the plus side as early as next year,” predicts Marjan Senjur, a lecturer at the Faculty of Economics.

“We’re now on the rails to recovery. People could look into the future optimistically and say: ‘Ok, we’ve contributed funds again, but this needs to show some benefits,” comments Senjur upon Slovenian bank rehabilitation in an interview with MMC. Senjur was the president of the fiscal council in Pahor’s government and, prior to that, served as the minister of economic relations and development in Drnovšek’s third prime ministerial term, keeping the function in Bajuk’s government, too. “A lot depends on the last quarter of the year, the economy has been improving. It’s all just speculation, but the next year could be quite good. I’m not talking about quick economic growth, but we could avoid negative growth. This possibility exists already in 2014.”

There was no other solution

Senjur does not see a point in “crying over” the fact that every citizen now owes 2,879 euros in debt, since “there was no other solution”. Due to the fact that Slovenia has been struggling with the economic crisis for 5 years now, this needs to be seen as a way out of recession. Since 2011 and particularly from 2012 onwards, it has become clear that one of the extreme solutions to Slovenia’s problem lies in re-nationalization of Slovenian banks and companies, although – says Senjur – the then government still dreamt about other solutions that would not require money from the government. “This is why the decision had been postponed for almost a year and a half. What’s happening now is a re-nationalization of banks and companies that had been some sort of pawns in their balance sheets,” explains Senjur, adding that “what we’re paying now is not direct taxpayers’ money, but rather an investment of the country – we’re the country – and our money into the economy. We’re hoping to see this money returned, sooner or later. Some failed investments will be sold, some will be restructured and the money will be returned,” says Senjur, who expects this to be an investment that will be reimbursed to Slovenia.

The money hasn’t been thrown away, it has been invested!

“This is necessary. We shouldn’t see this as money that has been thrifted, saying ‘we’ve thrown away money yet again’. No, we’ve invested it. If this is a good investment will depend on whether or not we put the economy back on its feet. First the banks and then the economy; if the latter restarts successfully, this will be an investment that will repay the money.”

Time for recovery

According to Senjur, another question is economy rehabilitation, since a lot depends on whether of not the economy will start recovering. “In these times, there is a realistic possibility for the economy to start recovering, to cleanse its ‘losers’, bankrupt companies. The main reason for recovery lies in a slight conjuncture in the west, where we sell our exports. We could expect to see the economy starting to recover next year. But for now this is just speculation,” remains optimistic Senjur.

Bad loans? We’re like that!

Have we really put an end to bad loan practices? Professor Senjur responds to our question: “We don’t know. It’s not about replacing all management boards and supervisory boards, as the NKBM and NLB banks both have brand new boards. These are new people, we can replace them with new ones; we can do this every year, but it would lead nowhere.” Senjur believes these are old, recurring practices. “But it’s us! These practices haven’t entered from outside. We’re like that.”

We’re not Scandinavia

Senjur sees the solution in long-term stability, especially in terms of company and bank management, and the government shouldn’t keep changing the concept every year; banks and companies should have long-term management and supervisory board members. “If we succeeded in this, we would solve many things. We’re not as bad as we depict ourselves, but we’re not perfect either. We’re an average developed country, we’re not Germany or Scandinavia. Our capability is at the level of an average developed country, that’s a fact,” points our Senjur realistically.

Estonians have Scandinavia to rely on

Estonia’s public debt, for example, only amounts to 7% of its GDP, since the country’s economy is influenced by Scandinavia, especially Sweden and Finnland. “They have a policy of strict market solutions and a poorly developed system of social security. If we had such patrons to rely on, on their banks, we might have had an easier time. But we’re not such a country. We have no one to rely on, we can’t say ‘we’ll rely on Austrians, we’re a backing for their markets’. Estonians are a good and a cruel example at the same time, since the fluctuation in their economic growth is up to 10 per cent, also on the downside. When the economy needs to shrink, they simply shrink it, since their civil society isn’t as well-developed as ours. We have strong trade unions and the civil society. If we just shrank salaries and public expenditure, they would be shocked by what happened in 2012; it’s not wise to shrink these things,” argues Marjan Senjur in the interview with MMC.

We’re not as bad as we depict ourselves, but we’re not perfect either. We’re an average developed country, we’re not Germany or Scandinavia. Our capability is at the level of an average developed country, that’s a fact.

We shouldn’t see this as money that has been thrifted, saying ‘we’ve thrown away money yet again’. No, we’ve invested it. If this is a good investment will depend on whether or not we put the economy back on its feet. First the banks and then the economy; if the latter restarts successfully, this will be an investment that will repay the money.