For years, the 100-meter mark remained a magical, unreachable milestone in ski jumping – the dream of many talented athletes. But in 1936, an Austrian ski jumper made sports history by finally breaking that barrier – and he did it in Slovenia.

Even before World War II, the ski jumping competition in Planica was a hugely important annual event. Spectators from around Slovenia, including many schoolchildren, rode the train to Planica to watch the world’s best ski jumpers in action. Many others listened to the competition on Slovenian radio, which carried it live.

And in 1936, the spectators were in for a special treat. In past competitions, Norwegian and Polish jumpers had approached the fabled 100-meter mark, making it to as far as 99 meters. Over the past year, however, Stanko Bloudek, the engineer who had already worked on the Planica ski jump, made some important improvements. The combination of the ski jump’s design and the favorable springtime wind conditions in the narrow Planica valley finally made a 100-meter jump appear within reach.

But the conservative Norwegians, seen as the most likely to set a world record and break the mythic 100-meter milestone, weren’t happy with the modified ski jump. Citing safety concerns, they decided not to take part in the competition at all. Birger Ruud, the current world record holder and Olympic champion, was among those who stayed home.

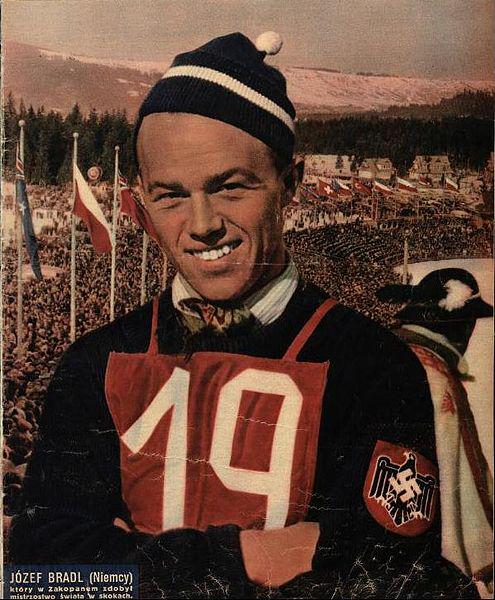

It was an 18-year-old German-born Austrian competitor by the name of Josef “Sepp” Bradl who saved the day in front of an audience of 15,000. In a perfect jump, he set the world record, landing at the 101-meter mark. His remarkable performance guaranteed his place in sporting history as the first human to jump more than a hundred meters.

Because of pressure from the International Skiing Federation (FIS), no competition was held at Planica the following year; ski jumping only returned to Bloudek’s Giant Jump in 1938 under the guise of “training jumps.” Bradl managed three jumps over one hundred meters that year, and telegraphed his mother with a simple message: “Just imagine – I jumped 107 meters and I’m still alive!”

The crowds adored Bradl. In addition to his passion for the sport, he also possessed the common touch. He became a lifelong friend of the local Slovenian boy who had helped him carry the record-setting skis to the top.

Bradl set several more world records in the years to come, and later became a coach of both the Austrian and the German ski jumping teams. He also ran a popular inn with his wife in the Austrian Alps, but he remained best known for his historic achievement, accomplished in a remote Slovenian valley when he was just 18.