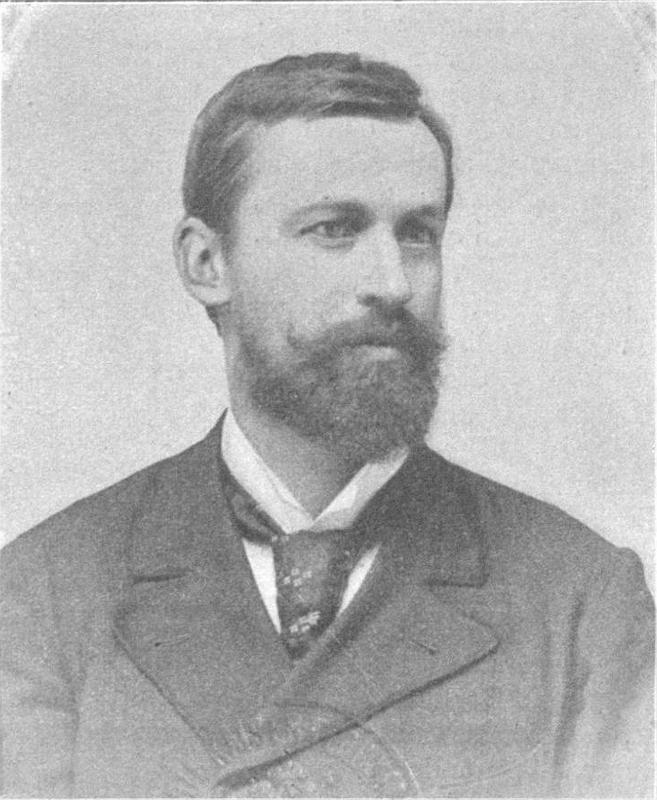

In 1865, Max Fabiani was born in the small village of Kobdilj in the Karst, a windswept limestone plateau in what is now southwestern Slovenia. His parents, of German and Italian ethnicity, were prominent local wine producers who also owned a year-round water source and made money from the sale of that precious liquid in the otherwise dry region.

Fabiani grew up in an environment where three languages were widely spoken: Italian, German, and Slovenian. For the rest of his life, his worldview and his architecture were shaped by the multicultural and multilingual environment of his youth.

Like many budding architects in Austria-Hungary, Fabiani moved to Vienna to study his craft. After graduating, he traveled extensively around Europe and was inspired by the continent’s most important architectural masterpieces. After his return to Vienna, he joined the architectural office founded by Otto Wagner, a pioneer of the “secession” style of architecture, the Viennese form of art nouveau.

In 1895, a strong earthquake struck Ljubljana, demolishing many old buildings in the central part of the town. In the aftermath of the quake, city authorities held a competition for a plan to reconstruct Ljubljana, and thanks in part to Mayor Ivan Hribar, Max Fabiani was chosen to tackle the project. He was favored by the mayor because of his familiarity with Slovenian culture.

Fabiani came up with a grid-based urban master plan for the city. Some parts of his proposals, including a ring road around Ljunljana, were so much ahead of their time that they were never realized. (His plan to lower the railroad tracks near the central train station isbeing considered today.) Much of Fabiani’s vision did come to life, however, and the architect ended up designing a number of imposing buildings in the style of the Viennese secession. The ornate splendor of Fabiani’s buildings symbolized the growing political and economic influence of the Slovenian national movement within Austria-Hungary. His architecture helped to transform Ljubljana from a provincial town into a Central European city.

In the wake of his successful work in Ljubljana, Fabiani was invited to design buildings throughout the Empire. Among other projects, he designed the Slovenian National Home in Trieste and the Slovenian House of Trade in Gorizia – both buildings became focal points for the Slovenian communities in the two cities.

World War I meant the end of Austria-Hungary and the cosmopolitan environment that had made Fabiani so comfortable. After the war, he declined an offer to teach architecture in Ljubljana, and settled in Gorizia, which was now a part of Italy.

He indulged his passion for inventions, most of which were too far ahead of their time to be realized. He patented several airplane designs, as well as a chainless bicycle. In an era before air conditioning, he even proposed a system of pipes that would have brought fresh mountain air to the Italian city of Milan.

In 1935, Fabiani became the mayor of Štanjel, a village in the Slovenian Karst, then a part of Italy. During his time in office, he designed a garden, a pond, a pathway, and fortifications around the village. When World War II swept through the area, Fabiani used his knowledge of the German and Slovenian languages to save the village from the Nazis, while also maintaining good ties to the Slovenian anti-Nazi resistance.

After the war, Štanjel became a part of Yugoslavia, and Fabiani returned to Gorizia, which remained in Italy. Because of the Cold War, communications between the two sides of the border were limited. When his Slovenian colleagues heard that Fabiani had died, they arrived in Gorizia with a wreath, only to find him alive and well.

Two years after Fabiani’s actual death - in 1962 -, his remains were moved to Kobdilj, the little village where had been born almost a century earlier. Meanwhile, his architectural legacy continues to live on in numerous books, documentaries, and exhibitions - as well as the magnificent buildings he designed throughout what was then Austria-Hungary.