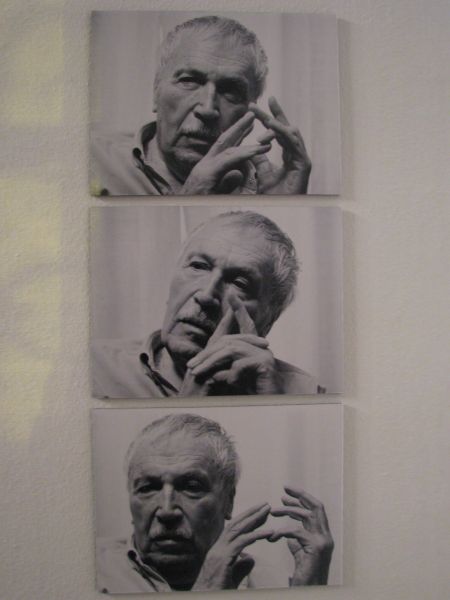

They are among the most striking portrayals of man’s inhumanity towards fellow man. Zoran Mušič’s haunting depictions of concentration camp victims made the Slovenian-born artist famous well beyond his homeland, but they were also deeply personal: They were based on his own experiences as a prisoner in Dachau.

Mušič was born in 1909 to Slovenian parents in the village of Bukovica near Gorizia. At the time, the area was under Austro-Hungarian rule and was characterized by a hodgepodge of Slovenian, Italian, and German culture. When World War I broke out and the Vipava Valley found itself near the Isonzo Front, Mušič’s family moved away from the conflict, first to Italy and then to Austria. The chaotic political conditions during and after the war forced the family to change residence on short notice, until they finally settled in the newly-established Yugoslav state.

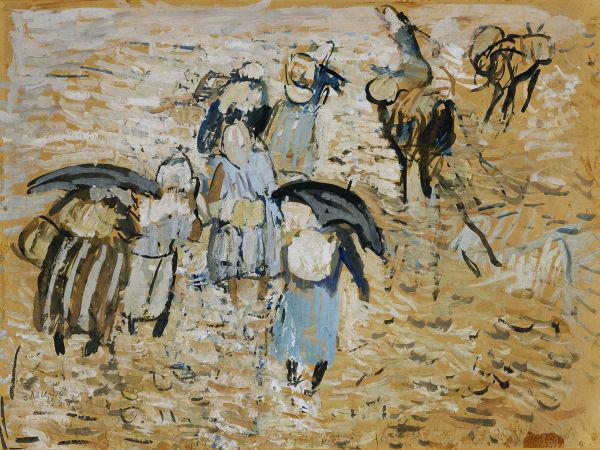

The interwar years represented a rare period of stability in the young Mušič’s life. He pursued his passion for the arts by enrolling at the respected Academy of Fine Arts in Zagreb, Croatia, and spent some time in Dalmatia and Spain, where he was inspired by the stark, arid landscapes of the Mediterranean. Later, these southern European motifs would feature in his famous works. While in Spain, he also familiarized himself with the works of great masters such as Velasquez, Goya, and El Greco.

Mušič’s world was shattered when another conflict swept through Europe. He spent much of World War II in the Italian city of Trieste, but was arrested by the Gestapo in 1944 and was sent to the notorious Dachau concentration camp near Munich.

At Dacahu, Mušič witnessed scenes of torture, hunger, suffering, and death. He survived the hellish conditions, but his troubles were not over. After the war, he returned to Ljubljana, but the newly installed Communist authorities viewed the cosmopolitan painter with suspicion. Fearing that he could become a victim of persecution, Mušič moved to Venice, Italy. (Several other Dachau survivors were later condemned to death in show trials.)

Mušič spent his postwar years in Venice and Paris. While he had struggled to establish an artistic career before the war, he emerged as a mature and respected painter after 1945.He first became famous for his portrayals of horses and the stark landscapes of southern Europe – the same scenery he observed as a young man in Spain and Dalmatia. Later, he used sketches he had made in Dachau to create a series of paintings poignantly titled “We Are Not the Last.” The paintings featured tortured, deeply pained human figures enduring unspeakable abuse at the hands of their fellow humans.

His remarkable paintings earned Mušič a number of awards and enabled him to exhibit at the prestigious Venice Biennale, Centre Pompidou, and various U.S. galleries. He was named Commandeur des Arts et des Lettres and Officier de la Légion d´Honneur by the French government and established a warm bond with French President François Mitterrand.

Mušič died in 2005 at the age of 96. While Slovenia considers him to be one of its greatest artists of all time, he has often been described as an Italian painter – a reflection of his cosmopolitan life affected by the whirlwind of the 20th century.