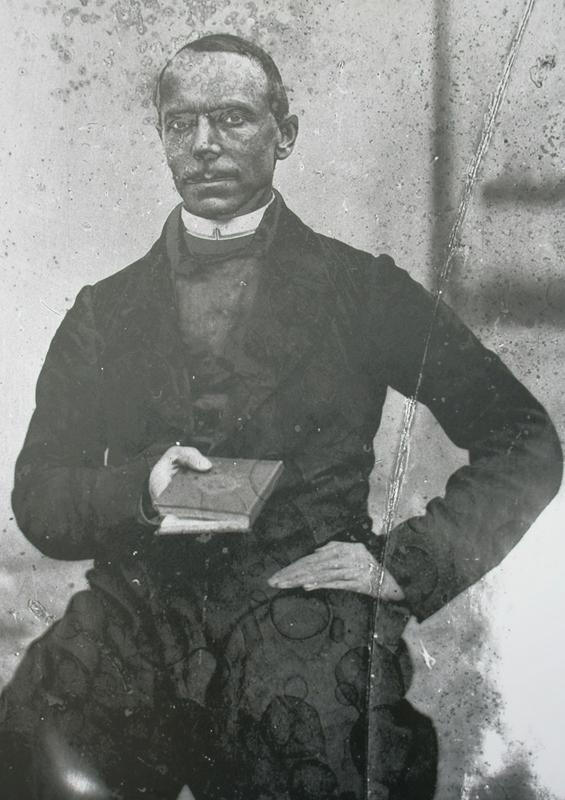

A lifelong thirst for knowledge and passion for innovation led a Slovenian priest named Janez Puhar to become a pioneer in the field of photography – even though he is yet to receive the recognition he deserves.

Born in the town of Kranj in 1814, Puhar had a talent for many subjects at school. He excelled in foreign languages, had a knack for science, and wanted to become and artist, but he ultimately followed his mother’s wishes and opted for a life of priesthood.

As a priest, Puhar developed an enthusiasm for a new technology that was sweeping Europe at the time – photography. The daguerreotype process had just been invented in France and Puhar spent months experimenting with it. He was determined to get rid of the expensive copper plates on which daguerreotypes were printed. In 1842, he came up with a brand new technique – and the first method of printing photographs on glass. It was based on Puhar’s own camera design and an innovate mix of chemicals treated with a sulfur candle. In addition to replacing copper plates with much cheaper glass, the new technique enabled a far shorter exposure time that made photography far more practical and enabled the taking of portraits.

In his work as a priest, Puhar frequently moved around Slovenia, and in the years flowing his breakthrough, he was living in the resort town of Bled. There, he was able to establish ties with wealthy vacationers from across Europe, who made sure that his invention was soon profiled by influential periodicals in several European countries. In 1852, he was even asked to send a sample of his photographs to the World’s Fair in New York.

Always an enthusiast rather than a professional inventor, Puhar registered his invention only after several others had also devised methods of photography on glass. Their techniques required longer exposure times, but relied on a more straightforward processes, and through the decades, Puhar’s breakthrough was slowly forgotten.

Puhar continued to tinker with photography. In the years that followed, he pioneered various techniques using many different kinds of media. He also made musical instruments, honed his craft as a poet and a painter, and observed the heavens as an amateur astronomer.

He died of lung disease in 1854, aged just 49. It’s likely that the fumes from the chemicals with which he worked contributed to his illness. However, many of Puhar’s photographs survive to this day. Along with the Puhar Prize, given annually to Slovenia’s top photographers, they serve as a reminder to a man whose inventive spirit left a deep - but often unappreciated - legacy in the art of photography.

Jaka Bartolj