In the 1980s, an avant-garde Slovenian design group decided to challenge Yugoslav political orthodoxy – and created a political firestorm.

The Relay of Youth was a Yugoslav Communist tradition. For decades, young Yugoslavs would pass a relay around the country and then present it to President Tito at a mass ceremony in Belgrade.

The relay continued after Tito’s death, but to a new generation of Slovenians, the tradition was becoming a laughable anachronism. Young people of the 1980s were increasingly liberal-minded and Western-oriented; to them, the spectacle was not just wasteful, but also a symbol of a failing ideology.

In 1987, it was Slovenia’s turn to design the baton and the official posters for the event. The winning design for the poster was produced by Novi kolektivizem (New Collectivism), the design wing of Neue Slowenische Kunst. NSK, as it was commonly known, was an avant-garde group with a reputation for challenging Communist orthodoxy.

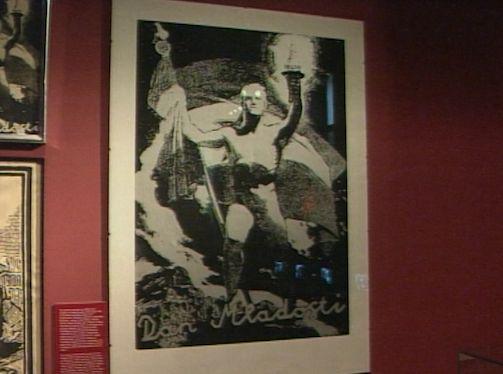

However, there was nothing unusual or provocative about the group’s winning poster – at least at first glance. It featured an athletic, blond-haired man scaling a boulder holding a large Yugoslav flag in one hand and a baton in the other. The poster could have easily passed for a classic work of orthodox Socialist Realism -- but there was a catch.

When a Serbian engineer named Nikola Grujić saw the poster, it seemed strangely familiar to him. He remembered seeing it in a history book. Indeed, when he checked the book, he saw the same poster – or one that looked strikingly similar. Instead of the Yugoslav flag, the blond man in the book was holding a Nazi flag. Instead of the baton, he was holding a Third Reich torch. All other imagery was more or less the same.

In a breathtaking act of political satire, Novi kolektivizem had remade a Nazi poster, turned it into a Communist one, submitted it to the national competition – and won. It was the ultimate condemnation of official Communist iconography.

Grujić immediately reported his discovery, and the poster’s creators, along with the members of the committee that selected it, were interrogated by the police. The liberal magazine Mladina was even prevented from reproducing the poster on its cover. Forceful condemnations of the group’s “provocation” came from all parts of Yugoslavia.

However, a year later, local prosecutors in Slovenia decided not to press charges against Novi kolektivizem, citing their freedom of artistic expression. The era of political liberalization – known as the Slovenian Spring -- had arrived.