In the 19th century, a Slovenian civil servant named Lovrenc Košir came up with a remarkable idea to simplify the postal service. He was the first person in the world to officially propose a postage stamp. But because of the complacent Austro-Hungarian bureaucracy, his idea was ignored, and a British postal official is now commonly credited with the invention of the postage stamp.

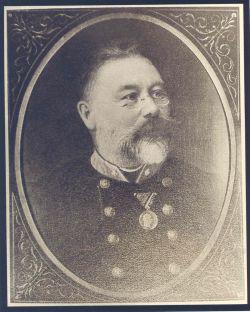

Košir was born in 1804 not far from the ancient Slovenian town of Škofja Loka in the mountainous Upper Carniola region. He was an excellent, intellectually curious student and was able to join the Austro-Hungarian civil service soon after graduating from a prestigious Jesuit school in Ljubljana.

In the 1930s, Košir, who spoke five languages, got a job in the accounting department of the Austrian postal service. He soon discovered just how inefficient the postal service really was. Its collection methods were so complicated and oversight so lax that large amounts of money routinely went uncollected.

Košir decided to reform the system by introducing a brand-new device: stamps that would be sold in booklets, each a different color indicating its nominal value. It was a revolutionary idea, closely resembling the system we use today -- and it was promptly rejected by Košir’s superiors.

Košir had underestimated how deeply bureaucratized the Austrian postal service was. He was also unaware that some officials had a vested interest in the inefficient but conveniently flexible status quo. Because his ideas posed a thread, Košir was not just ignored but also demoted to a lower paying civil service position.

The story did not end there, however. A few years later, he shared his idea with a British traveling salesman. Košir’s proponents claim that the salesman shared his idea with Rowland Hill, a British postal reformer who went on to create the world’s first postage stamp.

Košir tried to claim authorship of the invention at several international conferences, but was not successful. He went on to write a Croatian-Hungarian dictionary, but ultimately died alone and destitute in a Vienna poorhouse, suffering from tuberculosis, in 1879.