On the must-see list of almost any tourist visiting Slovenia, Bled is now one of the country’s premier tourist destinations. The tourist industry supports the town’s economy and the hotels and restaurants along the lake do a brisk business.

But it wasn’t always like this. In the first half of the 19th century, Bled was just another place in rural Slovenia. The island Church of the Assumption in the middle of Lake Bled did attract pilgrims, but despite the area’s beauty, there was no tourism to speak of. Only farms surrounded the lake.

Then, in 1852, Arnold Rikli came to Bled. The son of a wealthy Swiss family, he and his brothers had founded a factory near the Austrian town of Klagenfurt. However, Rikli suffered from a number of ailments, and his health problems were exacerbated by the chemicals used in this factory, so he sought to restore his well-being in the pristine nature surrounding Lake Bled. The local microclimate evidently did the trick and Rikli’s health improved dramatically.

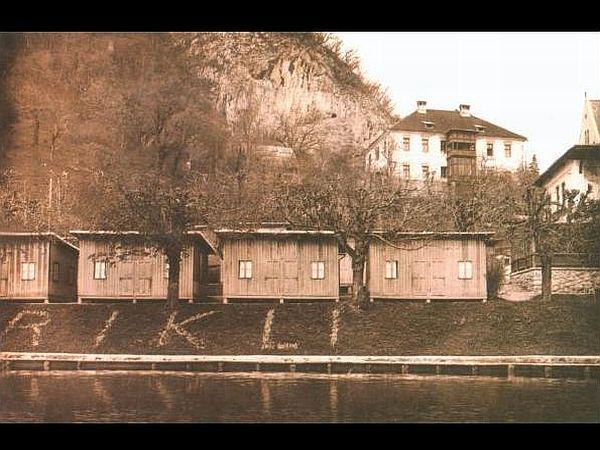

Impressed with the results, Rikli decided to share the healthful properties of Bled with others. He left the factory to his brothers and opened a sanatorium in Bled devoted to what he called “helio-hydrotherapy.” The regiment was strict: The guests of his camp were woken up at around 5 A.M. to go on an early morning walk. They spent much of the day in various types of baths – steam baths alternating with cold baths full of mineral water from nearby springs. They also sunbathed – itself a novelty at the time – and did it in the nude, which many considered downright shocking. (Some scholars believe this may have been the beginning of nudism.) Drinking and smoking were forbidden, and most of the meals were vegetarian.

The locals didn’t know quite what to make of Rikli. His methods were seen as eccentric and the occasional nudity of his patients scandalous. In return, he was equally ambivalent about the locals: He reportedly treated them with condescension and never bothered to learn the Slovenian language.

Still, Rikli put Bled on the tourist map. The number of visitors to his sanatorium kept increasing, helped in part by new railroad links. Under Rikli’s orders, swimming platforms, trails, and promenades in parks were built. In the 1890s, he opened a brand-new sanatorium building that also housed his offices. His cures attracted the rich and fashionable from across Europe.

Soon, however, Bled became famous in its own right. Rikli died in 1906, and the fashion for strict health regiments was soon on its way out. The turmoil of World War I meant the end of his sanatorium. But Bled itself kept growing and is now one of Slovenia’s top tourist destinations.

Today, visitors may notice a monument devoted to Rikli in one of Bled’s parks. They may try out some therapies based on Rikli’s old methods at one of the hotels. They may also see his dilapidated villa, owned by a shady businessman. But Rikli’s true legacy is all around them: He was the one who created Bled as we know it – a major resort attracting tourists from around the world.