In the mid-19th century, a researcher browsing through old books in a Ljubljana library made a startling discovery. He had stumbled on several Slovenian-language poems, prayers, and a glossary dating back to 1428. The texts - now collectively known as the Stična Manuscript - were among the first ever written in the Slovenian language; they were the work of a monk from the Cistercian Stična monastery in Slovenia’s Lower Carniola region.

The monastery was founded in 1136 on the initiative of Pellegrinus I, the Patrirch of Aquileia. The Cistercian order has its roots in France, and its members, known as the White Monks, came to the monastery from across Europe. According to legend, the building’s walls kept collapsing during the construction, but a bird finally convinced the monks to build the monastery on a different spot nearby.

The bird’s advice was apparently sound, and the monastery soon became a major center for education in the region. The 16th-century composer Jacobus Gallus and the polymath Anton Tomaž Linhart both studied with the White Monks. Through the centuries, periods of relative peace were frequently shattered by the Ottoman Turks, who made frequent incursions into the Slovenian Lands. Impressive fortifications built by the monks kept the monastery from being captured by the Ottomans. The main building also grew over the centuries, and became an attractive hodgepodge of Romanic, Gothic, and Baroque elements.

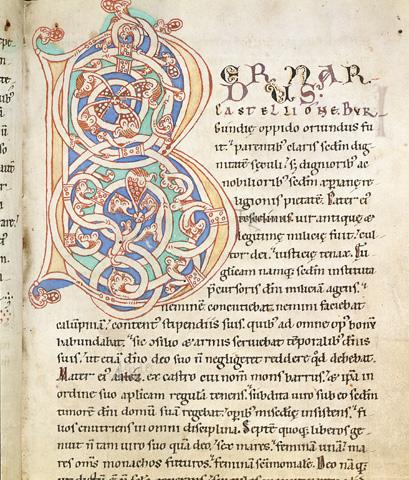

Some of the monastery’s most lasting works originated in the scriptorium, where monks spent many hours laboriously copying manuscripts. It’s there where a Czech monk wrote the famous Stična Manuscript. The work – written in the Czech black letter script – provides invaluable insight into the historical development of the Slovenian language at a time before Primož Trubar made his pioneering effort to standardize the numerous dialects spoken in what is now Slovenia. The glossary is now considered to be the first dictionary in the Slovenian language.

The Stična monastery also became a major regional center for the study of herbal medicine. The centuries-old tradition survived through the centuries, and was popularized by Simon Ašič, a 20th century monk who shared the monastery’s herbal traditions with a wide audience and made the local herbs available to pharmacies across the country.

The monastery’s continuity is remarkable; it managed to carry out its historic mission despite frequent political turmoil in the outside world. Its biggest challenge came in the late 18th century, when it was shut down by the Austrian emperor. However, it was reestablished a century later by monks from the area around Lake Constance and continued its work much like before.

When Communists came to power after World War II, large parts of the monastery were nationalized, and one wing of the building even hosted a public high school for several decades. The core of the monastery remained in Church hands, however, and the White Monks went on with their spiritual activity.

Today, visitors to Stična can tour the Museum of Christianity or visit the monastic pharmacy, which continues the Cistercians’ centuries-old tradition of herbalism by selling traditional remedies. Meanwhile, the monastery itself still plays an active role in the spiritual and cultural life of Slovenian Catholicism.