A man from rural Slovenia named Vladimir Vauhnik became an international spy and uncovered one of the biggest secrets of World War II.

Vauhnik was born in 1896 in the gentle hill country of eastern Slovenia. He grew up in a patriotic Slovenian family and was drawn to the military even as a young boy. He became a cadet and later enrolled in the Theresian Military Academy near Vienna. When World War I broke out, he loyally served Austria-Hungary in combat. By the end of the war, however, the empire began to collapse, and Vauhnik joined the newly constituted Slovenian forces. Led by the famed General Rudolf Meister, he fought to secure Slovenia’s northern border, which had been contested by Austria.

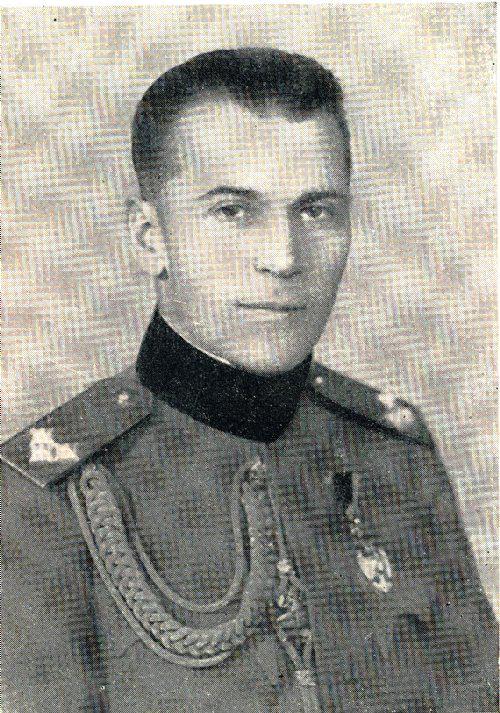

After the war, Vauhnik joined the army of the newly formed Yugoslav state and underwent further military training in France, where Charles De Gaulle was a classmate of his. Vauhnik attained the rank of colonel, and in 1939, he was named Yugoslavia’s Military Attaché in Berlin.

During his stay in Germany, Vauhnik turned out to be a naturally born spy. He maintained contacts with a number of women – often the girlfriends and relatives of high-ranking German officers, as well as the owner of an inn frequented by SS officers. It was this network that enabled Vauhnik to keep the Yugoslav authorities up-to-date about the plans of the Nazi government, including persistent rumors that Germany was planning to attack the Soviet Union.

In April 1941, Vauhnik made his most important discovery: That Germany was about to occupy Yugoslavia. Days earlier, a coup in Yugoslavia had resulted in the installation of an anti-Nazi regime, prompting Hitler to devise a secret plan to invade and dismember the country. (Vauhnik had warned against the coup, wanting to delay it until Germany went to war with the Soviets.)

When Vauhnik learned of Hitler’s plan, he immediately alerted the government in Belgrade. He even predicted the date of the invasion. The Germans were stunned by the accuracy of Vauhnik’s espionage, and Hitler reportedly railed at the cunning of the Yugoslav attaché. Still, Germany’s invasion turned out to be a success, and the Slovenian spy ended up being tortured for weeks by the Nazis.

The Germans ultimately forced to join the armed forces of the Nazi puppet state of Croatia. What they didn’t know was that his career as a spy was far from over. Disgusted by the crimes of the Croatian regime, Vauhnik fled to Ljubljana, where he organized links with the British intelligence. His espionage work gathering continued even after he switched sides and joined the royalists Chetniks. He became an influential Chetnik officer, but his links to the British were discovered by the Gestapo. Fleeing almost certain death, Vauhnik escaped to neutral Switzerland.

After the war, Vauhnik refused to live in Tito’s Yugoslavia, preferring to immigrate to Argentina instead. Even thousands of miles away from his homeland, however, his image as a master spy stayed with him: Some Slovenian émigrés in the South American country accused him of spying for the Soviets.

Vladimir Vauhnik died in 1955.