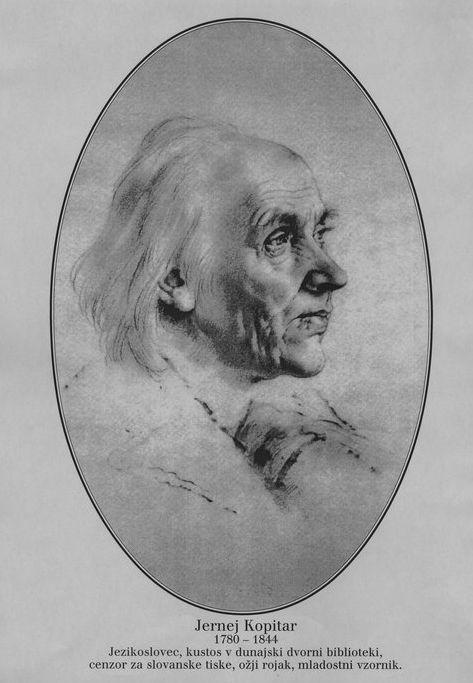

The Slovenian people tend to be proud of their language, which has, for centuries, been the cornerstone of their national identity. This passion has given rise to a number of notable linguists with international reputations, but in many ways, the work of Jernej Kopitar stands apart. The 19th century linguist left a lasting impact on not one, but two languages.

Kopitar was born in the village of Repnje, north of Ljubljana, in 1780. His father was the local mayor but both of his parents died, probably of cholera, when the young Kopitar was still only 14 years old. But he was a gifted scholar and was able to graduate from the lyceum in Ljubljana, obtaining what was then the highest education in the Slovenian lands. He had to learn both German and Latin – the two languages of instruction at the school.

After graduation, he became a private teacher and personal secretary to Sigmund Zois. A true man of the Enlightenment, Zois was involved in everything from literature to science. And as part of Zois’ inner circle, Kopitar met some of the leading Slovenian intellectuals of the day.

He eventually moved to Vienna, where he studied law, but was most well-known for his skill with Slavic languages. The authorities recognized his profound knowledge of the subject and he was soon named the chief censor for Slavic books sold in the Hapsburg Empire. He had an unusual talent for languages. In addition to several Slavic tongues, he eventually learned Greek, Italian, French, English, Romanian. He even mastered the basics of Hebrew, Arabic, and Sanskrit.

In 1808, Kopitar published the first modern grammar of the Slovenian magazine – a milestone in the history of the language. He was also the first linguist to conduct extensive research of the Freising Manuscripts, the oldest preserved document in the Slovenian language, and spent a considerable amount of time studying the origin of the Slavic languages.

Back home, however, Kopitar became eventually became most famous for his involvement in the “Alphabet War.” At a time, several linguists had tried to establish a standard way of writing the Slovenian language. Kopitar threw his support behind an alphabet proposed by a linguist named Adam Bohorič. His vocal support for the alphabet only exacerbated the split within the Slovenian intelligentsia and famously drew the wrath of the poet France Prešeren: “May a shoemaker [‘kopitar’ in Slovenian] stick to judging shoes,” he wrote in a poem mocking the Alphabet War. Kopitar’s favored alphabet was ultimately unsuccessful, as another system was chosen instead.

Some of Kopitar’s views about the future of the Slovenian language were also misguided. For instance, he envisioned the creation of a single South Slavic language, which would relegate Slovenian to the status of a dialect.

But in many other areas, Kopitar found lasting success and influence. He even helped to shape the Serbian language. He corresponded with the famed Serbian linguist Vuk Karadžić and, with his extensive insight and experience, helped to influence the shape of the modern Serbian language.

Kopitar died in 1844. Today, streets across Slovenia and even a neighborhood in Belgrade, the capital of Serbia, are named in his honor. They serve as a reminder of the legacy he left on two Slavic tongues at a time when they were just beginning to assume their rightful places among the world’s languages.