They may notice a sign indicating that they have passed into Baraga County. They may even see Baraga Airport (even though they’re unlikely to fly into what is merely a small general aviation airfield) or a lakeside shrine devoted to Baraga. And as they scan their radio dials, they may stumble upon the Baraga Radio Network, a Catholic network broadcast on several local radio stations.

Baraga - a missionary to the Native Americans

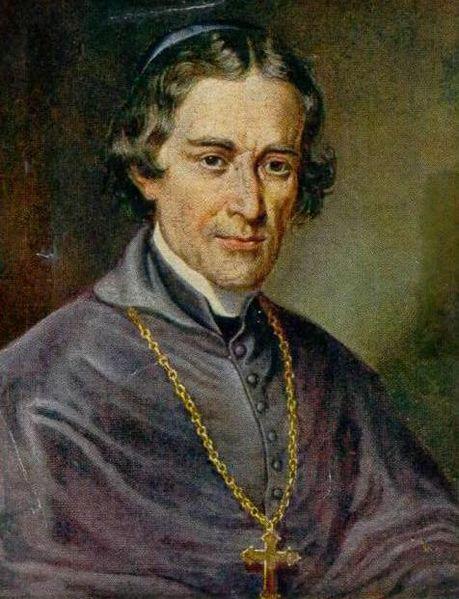

The name that has left such an imprint on this part of the world belonged to a Slovenian missionary: Friderik Irenej Baraga, known as Frederic Irenaeus Baraga after his arrival to the United States in 1830. Baraga, a native of Slovenia’s Lower Carniola region, had attended law school before becoming a priest, and was invited by Bishop Fenwick of Cincinnati to become a missionary to the Native Americans. His first stop was the Indian mission in Arbre Croche, Michigan. After a stint on Wisconsin’s Madeline Island, he founded a mission at L'Anse, in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula.

Baraga arrived to the region just as the region was opening up to white settlement. During his many years of service, first as a priest and then as a bishop, he encountered a wide variety of cultures and languages: From the Native Americans and French Canadians to recent European immigrants seeking a new life in the rapidly developing mining towns. But it was his work with the native population that left one of his most lasting legacies.

He converted most of the native population to Christianity

As a missionary in Arbre Croche, he not only converted most of the native population to Christianity and taught them European agricultural techniques, but also wrote a prayer book and catechism in the Ottawa language, the first book ever published in that Native American language. Later, while heading a mostly Native American and French-Canadian congregation on Wisconsin’s Madeline Island, he wrote a comprehensive grammar of the Ojibway language, titled Theoretical and Practical Grammar of the Otchipwe Language, and followed it with a complementary dictionary. (He nearly lost the manuscript when his sleigh broke through the ice on his way to Detroit. It wasn’t the only time Baraga found itself in grave danger in the area’s wilderness. Once, when making his way cross a frozen lake with a Native American Companion, the ice broke and the two men found themselves on an ice floe moving precariously away from the shore. As recounted by Bernard J. Lambert in his book Shepherd of the Wilderness, only a last-minute change in wind direction saved the two men’s lives.)

Remarkably, he was fluent in at least six languages even before he mastered Ottawa and Ojibway -- including Slovenian, German, French, Italian, Greek, and Latin. Even his diary was multilingual, continually switching from one language to another.

He used snowshoes to travel to remote outposts

Baraga also published detailed descriptions of pre-Christian traditions and rituals among the Native Americans, including their hunting ceremonies, in a book that introduced many Europeans to Native American cultures. The depth of his commitment to Native Americans is implied by his nickname, the "Snowshoe Priest", which he had earned by using snowshoes to travel to remote outposts in the depths of winter, often at night – in a region that was still overwhelmingly wild and untamed. He cared deeply for his flock; according to Lambert, Baraga even purchased valuable agricultural land to prevent the Native Americans from being removed from it by the authorities.

Baraga ended his career at the very top of the region’s Catholic hierarchy -- as the bishop of the Diocese of Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan. His first residence was in Sault Sainte Marie itself, today a sleepy town best known for the busy Soo Locks, where ships travel to and from Lake Superior. He later moved to Marquette, the Upper Peninsula’s largest town, and made the final visit to his native Carniola in 1853. As Bernard J. Labert, Baraga was “greeted by the thunder of cannons and the joyful ringing of bells,” wherever he went on his several-month tour of his homeland. He even went to Rome where he personally presented Pope Pius IX with two copies of his dictionary. Baraga died in 1868 at the age of 70 and is now interred in a crypt in Marquette’s Cathedral of St. Peter.

Baraga is a candidate for sainthood

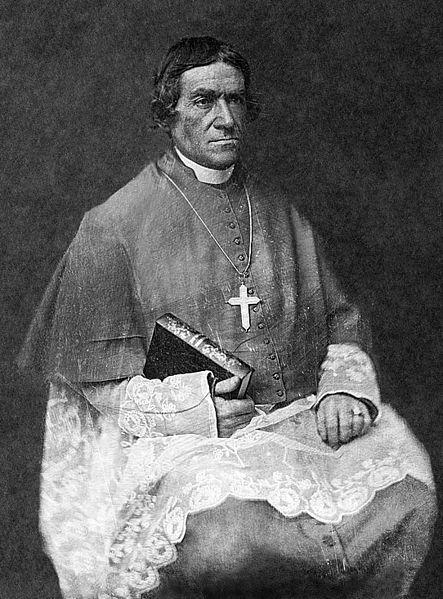

Baraga’s work inspired many other missionaries to come to the Upper Peninsula. One of them was Franc Pirc, a Slovenian who became Francis Xavier Pierz, eventually wound up in Minnesota, and also left a vivid legacy there, including the town name of Pierz, Minnesota. Baraga’s two immediate successors as bishops of Sault Ste. Marie were also Slovenian. Another man inspired by Baraga’s work was John Neumann, a Czech-born priest who immigrated to the U.S. because of Baraga, became the Bishop of Philadelphia, and remains the only male U.S. citizen ever to have become a saint.

Baraga himself was venerated in 2012 and is now a candidate for sainthood.

Jaka Bartolj