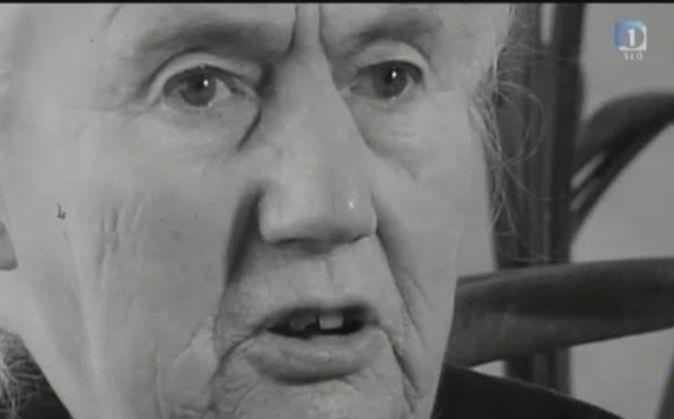

Nursing has a proud tradition in Slovenia, and these days, Slovenian nurses are in high demand in several European countries. But no matter where their profession takes them, they follow in the footsteps of Angela Boškin, Slovenia’s first professional nurse – a little-known woman with an impressive legacy.

Boškin was born into a poor family in the Slovenian village of Piuma (Pevma in Slovenia), now a part of Italy, in 1886. She was one of nine children growing up in difficult conditions, and as a young girl she did what many Slovenian girls had to do: She went to work as a servant girl, in her case to the imperial capital of Vienna.

Boškin had bigger dreams, however, and she eventually completed extensive training to become a nurse. At the time, nursing was still the domain of nuns in the Slovenian lands, but it was already considered a profession in Vienna. When she completed her training, Boškin joined a gynecological clinic run by Ernst Wertheim – an institution that was in many ways ahead of its time. There, she developed a strong interest in the care of newborns, and she quickly rose through the ranks of the clinic. Ultimately, she became an assistant to the head nurse.

World War I changed everything for Boškin. Like many other nurses, she was called in to tend to the wounded. Her skills and compassion were quickly recognized and she ended up as the head nurse of the Swedish Red Cross in Vienna.

The end of World War I saw the collapse of Austria-Hungary and Boškin left Vienna for Slovenia. After a stint caring for the war wounded, she became a nurse in the industrial town of Jesenice. At the time, Jesenice was struggling with poverty. Many babies received poor care, while those who were born out of wedlock were frequently abandoned. Boškin showed a passionate determination to help those who needed attention and she soon became a legend in the small town.

In 1922, Boškin moved to Ljubljana, where she set new standards of nursing care and passed on her skills to future generations of professional nurses. Eventually, she moved to Trbovlje, another struggling industrial town. There, her innovative approaches helped to drastically reduce infant mortality.

Boškin ended her career treating tuberculosis patients in Škofja Loka. She retired during World War II, and spent the next three decades in her native village of Piuma. She died in 1977.

For years, Boškin’s trailblazing career had been all but forgotten. Recently, however, some scholars and medical professionals have called for her work to be recognized. Boškin became the subject of a 2009 book by Andreja Korenčan, and a prominent nursing competition is now named after her. A plaque in Jesenice also draws attention to her impressive legacy – a commitment that changed nursing care in Slovenia and led Boškin to be dubbed Slovenia’s Florence Nightingale.