Although at first glance they offer sterile lists of taxes and services owed or paid to the local lord, in several respects the land registers present the everyday lives of serfs. One such example is food. In the listing of taxes we may ascertain that grains were the staple food of serfs (wheat, oats, barley, rye, and buckwheat), which they consumed in the form of bread and gruel, or along with poultry, mutton, pork, more rarely beef and animal products (eggs, cheese, curd and honey). During times when hunting and fishing were permitted, menus were enhanced with fish, crayfish and game, especially dormice, rabbits and birds. Farm dining tables also featured pulses (runner beans, beans and peas), vegetables (the indispensable cabbage and turnip) and fruit (apples, plums and pears). The descriptions of manors mention herb gardens, and in the coastal Primorska region groves of olives, almonds or apricots. Vineyards and taxes on grapes, must or wine are mentioned in all Slovenian wine-producing areas, and there was no shortage of wine on serf tables and elsewhere.

This article offers a brief presentation of the history of these land registers, and the contents of the records within them, with an emphasis on one basic human need – food.

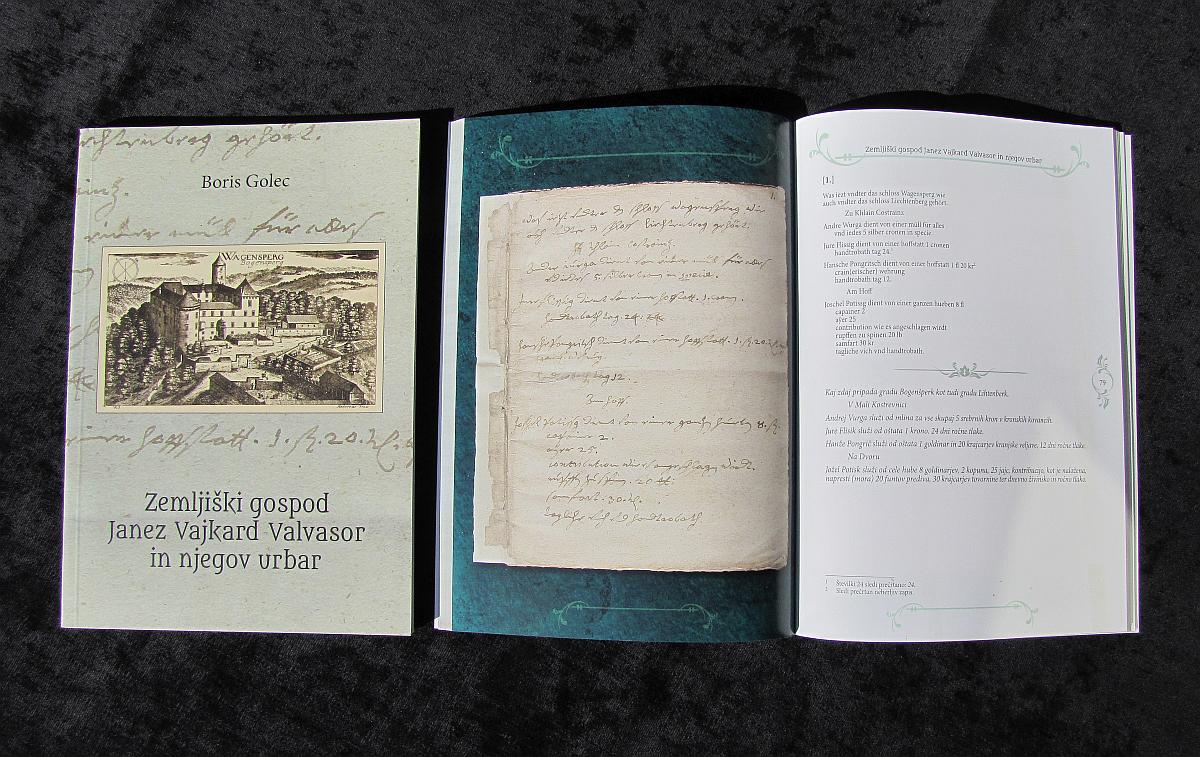

What land registers are, and when and why they were created

Land registers can be described as tables of the taxes imposed on serfs by the lord of the estate or landowner. They were created principally out of a need to review the landowners’ holdings and help in managing their estates, and thus were closely tied to the feudal system. In the Slovenian lands they appeared from the middle of the 13th century to the mid-19th century, covering the estates of both secular and church landowners. In that long period numerous economic, public, social and other changes were reflected in the land registers. Changes to the status of estates or land holdings, changes in owners and rights, or the introduction of new taxes, always served to create new land registers. There were also different types of land registers: the basic or main register was intended for long-term use, land register handbooks served to record the taxes that were actually collected, reformed land registers were made for possessions held by the rulers of the Habsburg hereditary lands, and the Stift (donations) registers were created upon the tax reforms carried out by the Empress Maria Theresa. Up until the middle of the 14th century, the land registers were recorded mainly in Latin, and then for the most part in German. However, in the Gorica area the land registers were written in Italian, while here and there these records were also written in Slovenian, in part or in whole.

Records in land registers

The main part of a land register was usually a census based on the names associated with farm holdings, organised by individual village. For each serf there was a list of taxes, corvée labour and servitude owed to the estate owner. Taxes were at first paid in kind, but starting in the 16th century they were paid increasingly in cash. Apart from taxes for the use of farms, serfs also paid owners for the right to use timber, graze cattle and hunt or fish. Through the corvée system, serfs worked on the manorial estate, performed haulage (of firewood, hay, produce, and mail), forest woodcutting, grapevine and fruit tree pruning, and sometimes also produced objects such as wine barrels. In the land registers it is also possible to find additional records of land holdings: descriptions of manors, manorial fields, gardens and orchards, registers of corvée, tithes or vineyard rights. Some even contain records that do not strictly belong in such registers: fair copies of charters and contracts, inventories of holdings, household equipment or tools, records of Turkish incursions and similar notes. The records in land registers are not always an accurate reflection of the actual economic status of a holding, since they reported on income in ideal conditions and not what was actually collected. At times the discrepancy between theory and practice was huge, as droughts, floods, freezes, large-scale epidemics, Turkish incursions and other misfortunes often caused significant reductions in output, which the land registers rarely noted.

Pictures of everyday life – diet in land registers

Although at first glance they offer sterile lists of taxes and services owed or paid to the local lord, in several respects the land registers present the everyday lives of serfs. One such example is food. In the listing of taxes we may ascertain that grains were the staple food of serfs (wheat, oats, barley, rye, and buckwheat), which they consumed in the form of bread and gruel, or along with poultry, mutton, pork, more rarely beef and animal products (eggs, cheese, curd and honey). During times when hunting and fishing were permitted, menus were enhanced with fish, crayfish and game, especially dormice, rabbits and birds. Farm dining tables also featured pulses (runner beans, beans and peas), vegetables (the indispensable cabbage and turnip) and fruit (apples, plums and pears). The descriptions of manors mention herb gardens, and in the coastal Primorska region groves of olives, almonds or apricots. Vineyards and taxes on grapes, must or wine are mentioned in all Slovenian wine-producing areas, and there was no shortage of wine on serf tables and elsewhere.

Additional notes in certain land registers disclose much more: what monks ate, and serfs too while performing corvée, and which exotic foods were subject to excise duty. On fasting days the monks of Bistra monastery mainly ate fish and crayfish that were imported (e.g., herring) or caught in Lake Cerknica (pike). They were very sparing with lard, since it was expensive, but each day they received a customary measure of white or red Teran wine. Those employed by the monastery were allocated meat two or three times a week, and on holidays even twice a day. Senior workers received white wheat bread, while servants received black bread baked from a mixture of wheat, rye, barley, oats, peas and beans.

During mowing time, the Jesuit serfs in Ljubljana had their own cooking woman who prepared meals for them by the meadow at Tivoli Manor. She cooked bean soup, pickled turnip with gruel and cabbage, and every day the mowers also received a piece of smoked meat, a roll of black bread and a measure of wine.

Although the land registers record the taxes paid by serfs, they also reveal records on those foods that only the rich could afford. These records are hidden away in the excise tariffs on goods that were taxed at numerous excise stations. Among the rare and expensive products one can find southern fruit (lemons, oranges, fresh figs), seafood (shellfish, pilchards) and numerous spices, such as pepper, cinnamon, nutmeg, ginger and the most expensive, saffron.

Danijela Juričić Čargo, Sinfo

Although at first glance they offer sterile lists of taxes and services owed or paid to the local lord, in several respects the land registers present the everyday lives of serfs. One such example is food. In the listing of taxes we may ascertain that grains were the staple food of serfs (wheat, oats, barley, rye, and buckwheat), which they consumed in the form of bread and gruel, or along with poultry, mutton, pork, more rarely beef and animal products (eggs, cheese, curd and honey). During times when hunting and fishing were permitted, menus were enhanced with fish, crayfish and game, especially dormice, rabbits and birds. Farm dining tables also featured pulses (runner beans, beans and peas), vegetables (the indispensable cabbage and turnip) and fruit (apples, plums and pears). The descriptions of manors mention herb gardens, and in the coastal Primorska region groves of olives, almonds or apricots. Vineyards and taxes on grapes, must or wine are mentioned in all Slovenian wine-producing areas, and there was no shortage of wine on serf tables and elsewhere.