As a centenarian, and a man who survived a concentration camp, I say that no economy and no party, left or right, can help, the only true thing is love.

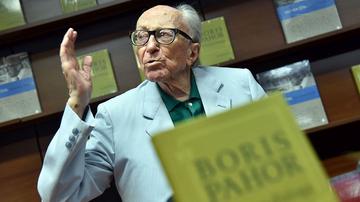

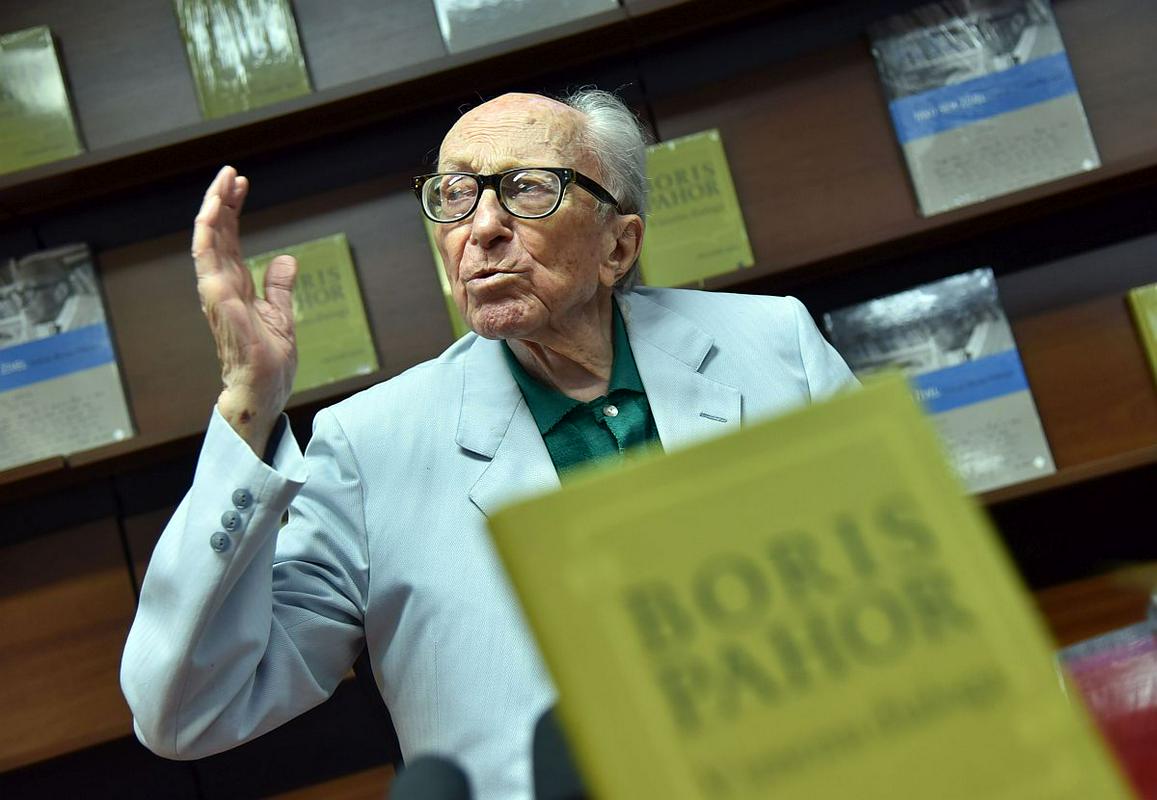

The further we move into the twenty-first century, the fewer people who witnessed the horrors of the twentieth are still alive. One of those few is the Slovenian writer Boris Pahor, aged 103, who spent fourteen months as a political prisoner in Nazi labour camps of Dachau, Dora, Harzungen and Bergen-Belsen. He devoted most of his literary oeuvre to the camp life and the systematic dehumanisation and humiliation applied by the Nazis. But his work extends beyond the literary sphere. In Slovenia and in the wider European area, he advocates anti-fascist views in an upright and determined manner, comments on polemical issues and warns that the horrors of the twentieth century could happen again in the twenty-first unless we strive for tolerance, understanding and dialogue.

Boris Pahor was born in 1913 in Trieste, which was still a port of the Austro-Hungarian Empire at the time. Those inclined to romanticise might think that this is the year when as many as three giants of world literature could be seen drinking cappuccino in this city on the same day, namely James Joyce, Robert Musil and Franz Kafka. But the "summer of the century", as some call this year, which was the last before mankind came to know a world war, predicted nothing romantic for Boris Pahor. As he recounts today, his life was marked by hunger. Due to World War I, he spent his early childhood in poverty which continued throughout his youthful years in the politically and economically unstable post-war 1920s and 1930s. But the peak of the hunger came about during World War II. First, he suffered scarcity as an Italian soldier in Libya (after World War I, the ethnically mixed Trieste became part of Italy, which is why Pahor was called up into the Italian army). His hardships continued after the capitulation of Italy, when he was a member of the anti-fascist national liberation army (which he joined himself), and later on as a political prisoner in Nazi labour camps. As he describes in Necropolis, his best known work about his life in the camp, he beat his way through the day in the camp with a piece of bread and a runny yellow soup with a piece of potato if you were really lucky.

Slovenian National Hall – a monument to culture

But the fascist politics, which influenced the work of Boris Pahor the most, was no less cruel than the hunger. After World War I, the western edge of the Slovenian territory was assigned to the Kingdom of Italy with the Treaty of Rapallo, even though the majority of the population was Slovenian. The same was true for Trieste, the largest Slovenian city (in which there lived more Slovenians than in Ljubljana) in the nineteenth century. Here, the inhabitants were the first to experience fascism. In 1920, the Fascists burned down the Slovenian National Hall in Trieste. The National Hall had a symbolic significance: Built in 1904, according to the plan drawn up by Max Fabiani, an architect from the Karst region (who was a friend of the successor to the throne Franz Ferdinand, and who also designed the plan for Palace Urania in Vienna). The National Hall was home to various Slovenian (mainly cultural) societies, as well as a café and a hotel. When it was build it was said that other nations boast with palaces, castles, churches and skyscrapers, but the Slovenians built a clean modernistic building, a monument to culture. Its burning meant that Slovenians were not welcome in the city centre. This act marked almost all Slovenian authors in this city, and everyone was writing about the burning of the National Hall as a prediction of the terrors that would follow. Pahor delved into the subject of the Hall arson in his work entitled Trg Oberdan (English: Oberdan Square), naming the book after the square where the National Hall stands.

Assimilation policy

It did not take long before the predicted terror reached Trieste (and the surrounding area). In 1922, Mussolini’s Fascist Party assumed power. They started executing their fascist assimilation policy right in the ethnically mixed area of the Slovenian territory’s western edge. They prohibited the use of the Slovenian language and prevented public life to all those who were not Italians. They did this by all means available, with torture and killings becoming increasingly common with each passing year. As early as 1923, the “Gentile” education reform came into force, which allowed classes only in the Italian language. Boris Pahor, ten years old at the time, has thus never been educated in his mother tongue and, in the end, completed his studies at the University of Padua.

The Slovenian language was a form of resistance that could cost one one's life. At the beginning of the 1930s, just as the world was becoming aware of the danger of fascism, the Slovenians living along the border area have already been experiencing it for an entire decade.

As a member of the resistance movement, Boris Pahor was arrested and brought to the German camps in 1944, at the end of the war. For the greater part of Europe the war continued into the fifth year, but Pahor already had as many as twenty years of persecution behind him. Pahor and his fellow camp prisoners had a red triangle pinned to their chests, which marked them as political prisoners (in 2015, the Italian publishing house Bompiani published his account on political prisoners, Triangoli rossi). Like all surviving witnesses, Boris Pahor was faced with the question of guilt, especially in Necropolis: By what logic did he survive the torture of the camp, but millions of others did not? Does his life mean that someone else had to die in his stead? Are all those who saw the end of the war responsible for the deaths of their fellow prisoners? What means are allowed when one is struggling for one's own survival?

Many, among which the most famous example is that of Primo Levi, could not bear this kind of introspection and took their life. But Boris Pahor is different. He says that he is pervaded with optimism and faith in love: "As a centenarian, and a man who survived a concentration camp, I say that no economy and no party, left or right, can help, the only true thing is love." The love towards our planet is also important – if the twentieth century fought against totalitarianism, the twenty-first century must fight against global warming, he says.

Eternal resistance fighter

Boris Pahor, still a committed activist, was very engaged already during the fascist regime and after the war. He was critical towards socialist Yugoslavia, the establishment of which was possible precisely due to resistance fighters like himself. He was one of the editors of the Trieste magazine entitled Zaliv (English: Gulf), which strived for a democratic organization of society and sovereignty of nations. The magazine was in conflict with the Yugoslav authorities (it was not possible to buy it in Yugoslavia, it was only accessible abroad), which culminated in 1975 in the "afera Zaliv" (English: the Gulf Affair). At that time, the magazine was published together with a brochure dedicated to Edvard Kocbek, a Christian socialist, who was prohibited to act publicly after the war in Yugoslavia. He was the first to publicly recall, in an interview, the post-war killings of about eleven thousand members of the Home Guard (Slovenian soldiers who collaborated with the Nazi Germany), who tried to run over to Austria, but the English returned them to Slovenia, where they were killed and buried in a hidden mass grave. For this reason, Pahor was banned from entering Yugoslavia, and only visited it again in 1981 to attend Kocbek’s funeral.

Today, Boris Pahor is one of the most translated Slovenian authors as well as one of the most important European observers, who still writes on a typewriter. He does not want to leave this part of the twentieth century behind him. Another such part is the custom which dictated that townspeople should greet each other on the street. Boris Pahor is vivaciously greeting his fellow townspeople on the streets of Trieste. This is one of the many reasons his sister calls him a "life optimist".

As a centenarian, and a man who survived a concentration camp, I say that no economy and no party, left or right, can help, the only true thing is love.