…what you do not say has never happened. Or will keep happening.

The biggest literary jury in Slovenia to date, comprising 18 literary historians and critics of several generations, gathered on the 25th anniversary of Slovenia’s independence and the silver jubilee of the prestigious national KresnikNovel of the Year Award, declared Kristalni čas (Crystal Time) by Lojze Kovačič as the best Slovenian novel of the last 25 years. The novel, which won the Kresnik in 1991 when the award was first bestowed, was described by the jury as "a true literary masterpiece by the greatest Slovenian writer of the 20th century". The central position which Kovačič’s works occupy in Slovenian literature is well-deserved. His literary oeuvre is impressive, both in terms of the themes discussed and the writer’s unique narrative approach. In his four-decade writing career, Kovačič kept exploring his past and present life, demonstrating through literary efforts that his individual story is part of a vast and all-embracing history of the 20th century and its breaking moments – a pattern underlying all tragedy.

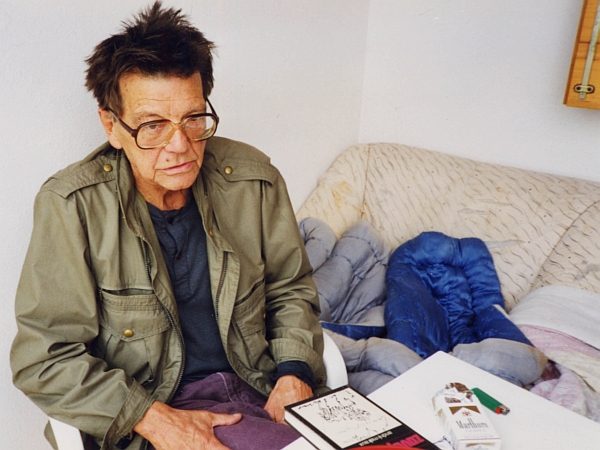

Kovačič wrote Crystal Time during the Slovenian Spring, when disease pushed him to the brink "between the illusion of death and the illusion of life". Bed-ridden, Kovačič would note down his emotions daily, and, as the scope of these notes grew, they evolved into the writer’s confrontation with himself, an account of his experiences, and an insightful self-reflection. In this autobiographical novel, a collection of journal entries, Kovačič returns to the past that he captured in his earlier works through the eyes of a boy and a young man, this time viewing it from the palimpsestic perspective of a grown-up, wise man on his way out. In Crystal Time Kovačič reopens a number of themes that he explores in almost all of his writings: death, God, the power of love, and, finally, creation as "the only excuse for living".

The most autobiographical oeuvre

The literary oeuvre of Lojze Kovačič – his novels, short stories, memoirs, diary entries, essays, and children’s stories – spans hundreds of pages. Whether we start exploring it from his first or last novel, or any other work, it does not take long to realise that throughout his writing career Kovačič was only interested in three things: man, life, and the world. It is pointless wondering whether any other topic could excite him as much. When readers become immersed in the enchanting melodies of his stories, closing in like a dark fugue or inspiring like light and airy sonatas, they can no longer break free. Kovačič writes in the first-person narrative, since his aim is to write the "story of only one life", the story of "a human being from the cradle to the grave". Kovačič persistently uses one protagonist, himself, and through studied modifications veil after veil covering his life is lifted to reveal a single destiny, his own. The writer is the subject and the object of his writings, his own hero, and the focal point of his stories. All other characters who appear next to him in different periods and circumstances of life only play supporting roles, although without them the main story – broken down into modest tales within his oeuvre – would not be as vibrant and persuasive as it is. Among Slovenian writers, Kovačič has left us with the most autobiographical oeuvre, a true love affair of life and literature.

"It's all in the language"

The works of Lojze Kovačič describe in detail all the stations of his life. He was born in 1928 in Basel, Switzerland, as the son of a Slovenian emigrant and a German mother. He had two older sisters, Claire and Margrit. His niece Gisela, Claire’s illegitimate daughter, also lived in the family home. Kovačič’s parents ran a fairly successful tailor and furrier’s shop in Basel. When his father refused Swiss citizenship, the family was deported to Slovenia in 1938. In Ljubljana the family lived in poverty, unwelcome strangers in a city where people spoke a language most of the family did not understand. In 1944 Kovačič’s father died of tuberculosis, and his mother, sister and niece were deported to a Carinthian refugee camp immediately after the war. Kovačič was only allowed to stay in Slovenia after several acclaimed culture workers had intervened on his behalf. By 1948, when he was drafted into the army, he had been homeless for some time and worked briefly as a journalist. During his military service, he was unjustly sentenced to half a year in the penal battalion. Finally back in Ljubljana, he graduated in German and Slovene but, being "morally and politically corrupt," he could not get a job. He worked as a freelance writer until 1963, and then took up the position of a puppet theatre and literature teacher. In 1997 he was appointed extraordinary member of the Slovenian Academy of Science and Art. He died in Ljubljana in 2004.

These biographical details make up the frame of the tragic fate that befall Kovačič and his family, as told in the novels Deček in smrt (The Boy and Death; 1968, revised by the author in 1999), Sporočila v spanju/Resničnost (Messages in the Sleep/Reality 1972), Pet fragmentov (Five Fragments; 1981), Prišleki (Newcomers, 1984–1985), Basel: tretji fragment (Basel: Third Fragment; 1989) and Kristalni čas (Crystal Time; 1990), to name the most important ones.

Basel and Ljubljana are the literary topoi of the author's process of recollection. Basel is "the lost place of childhood," and Ljubljana "the found place" of premature adulthood, maturity, and old age. Although upon arrival in his father’s land, the boy’s/writer’s world shatters into thousands of pieces (which the writer struggles to put back together almost until his death), Ljubljana is also the place where his new life, the life of a writer, begins. For Kovačič, writing becomes a way of making a modest living. Literature also unlocks a space of true freedom and, not least importantly, the meaning of life.

The experience of being a foreigner left an indelible mark on Kovačič ("If you are a foreigner, newcomer, an expatriate … you are only at home in your memory, in your head. Everything else is a foreign land."), and his literary pursuits are filled with signs of the linguistic duality of a man who was born into one language and taught another at a later age. When asked to describe what “homeland” was, Kovačič replied: "It’s all in the language. […] The language is the homeland and the homeland is where we speak this language." More surprisingly, Kovačič never thought of himself as a Slovenian writer. He said he was just someone "writing in Slovene".

A chronicle of the recent past

Lojze Kovačič did not go to great lengths to promote his work, which might be one of the reasons why his novels are only becoming available to foreign readers years after his death. Basel can now be read in German, Kristalni čas in Czech, and Resničnost in Hungarian. Prišleki (Newcomers), Kovačič's central work on the vortex of World War II and the post-war period, all the political, ideological, and social conflicts of the 20th century, a tragic chronicle of the recent past, has been translated into German, Italian, French, Spanish and Dutch. Recently the English translation of the first volume (by American translator Michael Biggins) was published (Archipelago Books, 2016), with the second and third part scheduled for publication in 2017.

To tingle your literary taste buds, here is a short extract from the beginning of the novel: It’s hot out there, I thought smugly, but in here there’s a breeze.All up and down the shady corridor the drapes kept battering against the windows and doors …God had chosen a totally ordinary, totally stupid day like this to send me on this train trip … far, far away to a country where Vati had lived as a child and then later as a slightly older boy.Up ahead, beyond the buildings and trees that were flying back into Basel like drizzle … on the far side of the clouds and the arrogant mountain that kept retreating ahead of us, no matter how much the train tried to reach it … on the far side of some mountain slope I was going to encounter all kinds of things that were appropriate for my age … whether those were toys or buildings, animals or people, cars or airplanes.At night nothing like it would ever have occurred to me … and I had never even dreamed about Vati’s country, let alone imagined anything like it during the day ….

…what you do not say has never happened. Or will keep happening.