Every fourth adult in Slovenia smokes, and one out of ten in the population of 15-year-olds is already a smoker. As a reaction to these statistics, and also due to implementing a new EU directive, the Slovenian ministry of health has been preparing a law on limiting the use of tobacco and tobacco-related products. The aim of the law is to lower the percentage of smokers in Slovenian population, yet the proposed measures have triggered numerous discussions about its justifiability and effectiveness. Since the draft of the bill had been open for public discussion up until recently, smaller amendments are likely to be made before the bill is passed to the government (and after that, the national assembly) for approval.

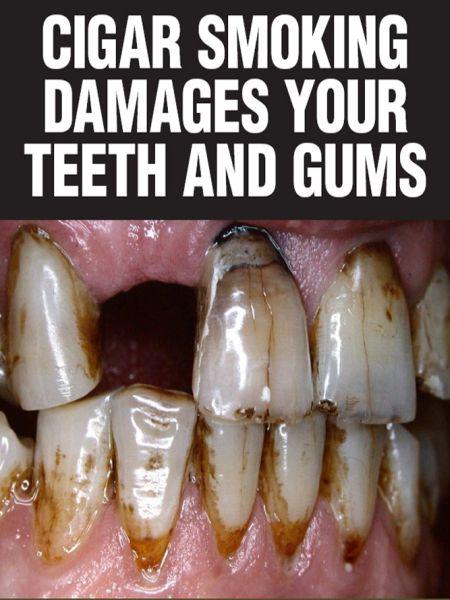

In short, the key measure of the bill is implementing a unified, plain packaging, which means that packs of all cigarette brands would look the same, including graphic, explicit warnings on health damage. Other measure are a ban on tobacco products with aromas and additives; a ban on online sale of tobacco and other tobacco products; a ban on smoking in the car when minors are present; a complete ban on advertising; establishing a tobacco centre and licences (including royalty payments) for selling tobacco products. The National Institute for Public Health (NIJZ) has greeted the proposed measures.

The opponents of the bill believe it would boost black market. That’s nonsense, says Robert Eckford, a representative of the world’s largest international anti-tobacco organisation, Tobacco Free Kids Campaign, who recently visited Slovenia. Eckford is the organisation’s assistant director for trade and investment law. In the past, he worked as a legal expert on unified tobacco packaging, explained Eckford in a short interview for MMC.

Mr Eckford, have you ever smoked?

Yes. I have. I smoked for two or three years in my teens and early twenties.

So you fit well in: most smokers started as kids and teenagers. One hardly finds any grey-haired tobacco lovers among first-time smokers.

Exactly, and good thing I realized in my twenties that smoking is not going to do me any good at all.

What had drawn you into it?

That is still a good question. I think it was seeing other people smoking, the public culture. There was also a lot less information about it in those days and a lot more advertising. This was before advertising ban, and I can still remember a lot of those adverts, they still stick out in my mind. That was very clever and some of the most innovative advertising was tobacco advertising. I can still remember three or four different series campaigns. I can still hear the music for Hamlet in my head. The big posters for The Lambert & Butler that contained smiling characters. There was no single thing that drew me in, there was just this pervasive culture. Smoking was everywhere.

Youth back then and youth today is still the key smoker segment of the population, no matter how many restrictions have been implemented and how much information have been circling around. You fight against it in your Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids. Can you tell me, at what age do kids light their first?

It is the teenagers. 80 percent of people who start smoking do it in their early teens. The rest of them start in their late teens and early twenties. Once you get past your early twenties, people generally just do not start smoking. Because you have already made that decision and you know about the addiction.

The tobacco industry is aware of this. What do they do about it - what have you learnt?

They do very innovative campaigns. A recent report came out that looked at targeting of youth in South America. The tobacco advert sits firmly alongside candy that is being sold to children. So you have a row of sweets and a big tobacco ad right next to it, and they clearly target children in that way.

They are also very clever on social media campaigns. Tobacco companies are starting to pay young people - and sometimes it is not payment in money, but in cigarettes and alcohol - to promote their brand of cigarettes online.

My organization is trying to counter that campaign, because it is very clever at getting underneath the sponsorship and promotion laws. Is it sponsorship? Well, not really. Is it advertising? Again, not really. They organize parties where the cigarettes are freely available. It is not the company that puts them there, but the young people they work with, they make sure the stuff is available as a part of the deal.

I was actually expecting the opposite answer: what is the industry doing to remedy the issue of smoking among the youth. Because even if you strip all the ethics away, it can still be a serious public relations issue for tobacco compaines. Addicted children and teenagers. I was not really expecting they agressively focus on them even further.

They are and they always will. Because if they do not, the industry dies. Smokers die and if you do not get new ones, the industry goes along into the grave. Furthermore, the industry has got such a poor reputation already, I do not think it really cares about it any longer. It does care about its reputation in the government, so it can influence the policies. It tries to represent itself as a responsible corporate entity. But in terms of public perception, it knows that the game is lost. So it is prepared to do anything that is essentially within the law. In the United Kingdom, the industry is pretty strict about staying within the law. It will do anything it can do, will push the boundaries, but there have been no real prosecutions of failure to comply with market controllers. The laws are strong, the enforcement is good, the government is ... I can say that it is not really a corrupt government. If something is done wrong, the law will be enforced. And this whole picture projects the image of corporate responsibility.

But there are many countries around the world where corporate governance is less strong, and there it flagranty breaches tobacco control laws. The enforcement is not that good, the governments may be a little more corrupt ... and so advertising laws are regularly breached around the world by the tobacco industry. They will push it as far as they can until they are exposed and then they crawl back. It is a war of attrition.

You may be aware of the allegations that are now being investigated around the British American Tobacco company, about bribing officials throughout Africa.

You say that in the UK, the law enforcement is good, the judicial system works. But still: kids get cigarettes. Obviously, the rules are being broken.

Kids get them from friends. Maybe some retailers are not as strong as they should be at checking identification. Some collect them around the house as their parents are smokers. You know: when you have a tobacco epidemic with a fifth of population that smokes, there is a lot of cigarettes around. Billions and billions. Kids get them. But that is not necessarily connected to the industry breaching advertising laws.

But with the latter fact in mind, and looking from a broader perspective: does tobacco control work?

Yes. It is good. Fundamentally, tobacco control works. But there is no silver bullet. There is no one single measure that is going to stop people from smoking. It is about the culture. As I was saying, when I was young, the culture was different. Now, the culture has moved on and the smoking has significantly reduced. Now it needs a comprehensive approach: it is about denormalising. It is about saying: this is not a normal product. You cannot sell it in a normal way, you cannot use it in a normal way. That will lead to less and less people wanting to start smoking, and more people wanting to give up. Giving up is extremely difficult. So control and prevention needs to be comprehensive, meaning a lot of different measures, targeting a lot of different psychological elements in order to get that one fifth of addicted population share down. The evidence is very clear, that it is the comprehensive strategies that look at the whole range of things and work together that work. The total is more than the sum of its parts.

So not a silver bullet, more like a rain of lead.

That is a good one, I will use that [laughs].

It seems that the tobacco industry is unique in a way. Even other risky businesses, like the gambling industry, tend to try and remedy some of the negative effects on the society. Casinos, for example, give out leaflets to customers informing them about possible negative outcomes, offer counselling therapies to addicts, or even shut down access to the individual that requests so. But with the tobacco it seems that they shun any attempts to adress addiction.

But could it be that this casino industry is obliged to do it by the law? I doubt they do it out of their own interest. The tobacco industry puts health warnings on the packets not because they want to, but because they are forced to. Also, you said something about unique industry. I would not say it is unique, I think it is extreme industry. All the things it does, all the tactics, you can see examples of that in food industry, or in gambling ... and so on. The tobacco industry has led the way in poor corporate practices, in lying about the effects of its products, trying to undermine legislation and public health regulations, lobbying governments ... in really putting profits before the harms. So, it is not unique, it is extreme.

Can the industry sue you? These are some pretty harsh accusations right here.

I am not making wild accusations, these are based on evidence. These words were said a thousand times before. They should be suing a lot of people for the things I am telling you now [laughs]. They lied about the harms. There were directors that stood before the congress and said specifically: we do not believe that nicotine is addictive. And when they had mountains of evidence before them - their own evidence - that has since been disclosed, it showed that they did know that nicotine is addictive. When you have CEOs of multinational corporations lying to the American Congress about these things, then I think I am fairly safe.

So far we have talked about the responsibility of the industry. But what about the responsibility of the other side, the people? No one puts the cigarette in your mouth. You do it on your own. And I am quite sure most of them are completely aware they are doing damage to their own bodies, taking away years from their life. But they choose to do so, because they take pleasure in it, or maybe add life to the years. They trade it for some extra pleasure in this sometimes painful existence. Why punish them for that?

There is a lot there to what you have said. First, individual choice. Well, no one is banning smoking. One country has tried it, Bhutan. It did not work, partly because it is a small country and everyone just got their cigarettes from outside anyway. Prohibition of alcohol in the USA did not work either. And when you have from 20 to 30 percent of a country that smokes, if you ban smoking, you are preventing a significant proportion of population from doing something they choose to do. So no one is banning smoking. Smoke-free laws are not about the people who choose to smoke, it is about the people around them. About second hand smoking, it is about not harming others, when someone chooses to harm himself. That is fundamental. Where those laws are extended out to public places, the open places, it is not about preventing individuals if they choose to smoke, but for denormalizing the products. Preventing smoking around children's playground is banned to prevent children from seeing it as a normal activity.

So that was about choice. For all the other things, we have the tobacco control laws. Prevention of promotion, sponsorship and advertising of smoking to stop the image of it as a normal product. Which it is not. Because there is no safe level. It is not like alcohol or sugar.

Not even a single cigarette per day?

Not even one. There is no benefit to it. All these other things can produce a neutral or beneficial effect if taken in moderation. Yet the cigarettes are just harmful. It all comes down to the idea, what is enjoyment. Why do people enjoy cigarettes? Your first one is not enjoyable, because it is not an intrinsically enjoyable activity. What is enjoyable, however, is the release of addiction. People enjoy it because their addiction is relieved. You feel nervous and tense, have a smoke and [sigh], that feels great, fantastic. Again, nobody is seeking - at this stage - to deny that. Restrict the harming of others? Yes.

Speaking about smoking and teenagers: a lot of secondary-school students here in Slovenia are told the story about the Death cigarettes. About the man who said, I know I will probably die because of smoking, but I choose so, and I enjoy it. So he put coffins and skulls on his brand of cigarettes and started selling them.

This is a part of the dynamic, why do people start smoking, and to your start of the interview, why did I start when I was a teenager? It is a complex issue, there is no one thing that makes somebody start smoking. One of them is obviously rebellion, and I am sure this is what people saw in the Death cigarettes, an emblem of rebellious activity. Not to mention that since James Dean cigarettes are still being projected by the Hollywood and the media, this is something that bad guys do. It projects a certain image. The essence is intrinsically a rebellious stage in your life.

But and yet: they are still individuals, they are still people, they still take information and make choices. In the end, this all is funding the profits of awful corporations, and teenagers need to see this to make sense, what their decision actually is - for their own sake. We can have rebellious individuals, but we need to take a look at population as a whole. And when we have countries that implement comprehensive tobacco policies, their smoking rates decline, and their teenage smoking rates with them.

You can still be a rebel without smoking.

You can still do something else, hang around on street corners [laughs].

The irony is, the owner of Death cigarettes essentially did what you are doing. He put a message on his package, telling directly: smoking kills. And he also succeeded in what today's ugly-image-covered packages aim at: declining the smoking rates. He had to shut down the endeavour in the end.

He was trying to make it cool, to play into the rebellion thing, the psychology. I mean, these packs did not look unappealing. They were made in a simple way, just like the Apple emblem is simple and effective. That is what the guy was trying to do. He was not trying to make an unattractive package. Now, plain packaging is mud brown, the color that people most associate with harm of the product. It is also combined with graphic health warnings. In all countries that have implemented it, they have very large health warnings. In Australia they are really quite disgusting. You do not want to be looking at the eyes or the lungs of the guy with cancer on death's door. It was shown to be effective on the behavioral level. For instance, they did studies in Australia before and after implementation of plain packaging, looking at how many people would display their packs outside restaurants and bars. There was a significant reduction of people that would be openly displaying their packs after implementation.

So the aim is actually not to disgust the owner of the packet, as he will continue smoking anyway, but to start hiding the packets, making them less normal.

It works on different levels. It harnesses the health warning that draws the eyes away from those flashy titles and to those graphic images. And it works on a progressive psychological level. If you are someone who wants to quit smoking, and in the UK 70 percent of people who smoke want to quit, addiction works with triggers. One of the triggers is the nice, attractive object that you hold in your hands, that feels nice, that moves in a nice way, that has elements that reassure you this is a nice product you are consuming, that is a trigger that reinforces the behaviour. But if you have in your hand a disgusting thing, plain, unattractive and draws your eyes to the health warning, it reduces the trigger. It is not a silver bullet, but it works.

Back in the day I heard people simply put their stack in another package and covered all the warnings away. How can you be so sure it works?

Because it does work. The covering thing did happen, it circled around in media telling it will not work because people will use extra packets. The evidence is that those leaves will not work. For instance, in most countries you have what is called brand sharing. So nothing else can have tobacco branding lines. You cannot have a T-shirt with Marlboro or a sleeve with Marlboro. You could potentially have a plain red sleeve and put your disgusting cigarette package in it. People can do that in a moment if they want to. But generally, they do not. Packs are convenient and also it is an acceptance, that what you have is an unattractive, harmful product. And that is how things work, when 70 percent of people want to give up smoking. All the evidence from Australia shows that the plain package is working. They have got the largest drop in smoking prevalence on record, during the period the plain package was introduced.

What about vaping? The vapers strictly oppose being treated like smokers, i.e. having the same tax burden, by reasoning that e-smoking is much, much less harmful. Would you agree with that?

There is quite a lot of debate around this. I think what you have is a situation where no one is wanting to ban vaping. That question is not on the table. The real question is, to what extent to regulate vaping. And it is sensible for governments to take a precautionary approach when we do not know what the evidence is around what could potentially be a very harmful product. Do you want to follow the example of tobacco, which was not regulated in any way and it was only decades after the harms had occured that you start to regulate and put your legs down. So I think it is reasonable for governments to take a precautionary approach, to say this is an addictive substance and therefore needs to be regulated as an addictive and toxic substance. And not to allow those companies to promote it in a way that will get another generation of people addicted to a product that no one knows what its long term harms are.

A recent VIP casualty of smoking was Mr Spock from Star Trek, Leonard Nimoy. He got the Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, even though he had stopped smoking 30 years before actually falling ill. That was his final message: stop smoking now, because it may already be too late. If you had heard that as a teenager, would you have lit the first one?

Would that add to the whole mixture of factors at the time? Could that have been the deciding element? I cannot second-guess my 18-year-old self. Maybe it would. But you can put that message to where we are today and hope that it will discourage at least some of the teenagers.

Aljoša Masten